Previous: “Animal Husbandry and Pig Farming”

Note: This article presents the medical and healing landscape of Gerasa by drawing from evidence spanning the 1st-2nd centuries AD, creating a comprehensive view of healthcare practices during this formative period of the city’s Roman development.

The Medical Landscape of Roman Gerasa

In the bustling streets of 1st-2nd century Gerasa, the approach to health and healing reflected the complex intersection of Greek medical traditions, Roman practicality, and local Semitic customs. The city’s position within the Decapolis and later the Roman province of Arabia meant that medical knowledge flowed through the same trade routes that brought goods and ideas from across the empire.

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), in his comprehensive Natural History (Books 20-32), documented hundreds of medical remedies derived from plants, animals, and minerals that would have been available to practitioners in cities like Gerasa. Many of these treatments relied on locally available materials from the fertile Jordan valley and the surrounding hills.

-> Learn more about Gerasa’s position in the ancient world in our [The Decapolis: Ten Semi-Autonomous Cities in Rome’s Shadow]

Understanding Disease and Illness

Medical understanding in Gerasa operated within the framework established by Greek physicians and adapted by Roman practitioners. The foundational theory, as described by Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC – 50 AD) in De Medicina (Books 1-2), centered on the balance of four bodily humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Illness resulted from imbalances among these humors, which could be corrected through diet, exercise, bloodletting, and various treatments.

Celsus, writing during the early imperial period, provides our most comprehensive contemporary source for Roman medical practice. His work describes how practitioners diagnosed illnesses by observing symptoms and applying treatments accordingly. In De Medicina (Book 3), he describes how Roman physicians perceived and categorized mental disturbances, offering a medical framework through which practitioners might have interpreted conditions that others, such as those described in the Gospel accounts, understood as demonic possession.

The presence of public bath complexes in Gerasa, including the substantial thermal facilities, indicates the Roman emphasis on hygiene as preventive medicine. Just like our modern spas, these facilities provided therapeutic services including massage therapy, supervised exercise routines, and controlled exposure to hot and cold water for treating joint pain and respiratory ailments.

Medical Practitioners and Their Methods

Professional medical care in Gerasa would have included several types of practitioners working within the Roman medical system. Medici were trained physicians who often originated from Greek traditions, while chirurgi specialized in surgical procedures. Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 29) describes the hierarchy of medical practitioners and notes that “medicine is the only art in which anybody who professes it is immediately believed.”

The Roman military presence in the region, documented through numerous inscriptions mentioning soldiers from units such as the Third Cyrenaic Legion, would have brought military medical knowledge to Gerasa. According to the document on Roman presence at Gerasa, military personnel including corniculares and various officers were stationed in the city, likely bringing with them the practical medical knowledge developed in Roman military medicine.

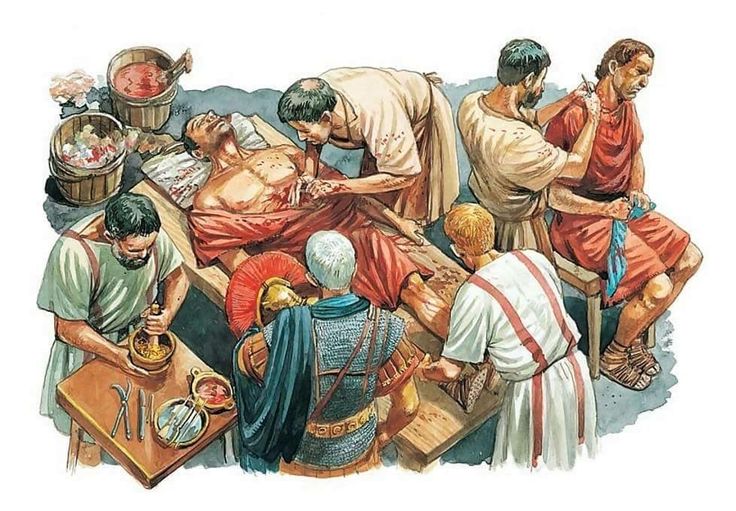

Celsus (De Medicina, Books 5-7) provides detailed descriptions of surgical procedures and wound treatment that would have been essential knowledge for any practitioner serving an urban population engaged in trade, crafts, and military activities. For example, he describes cataract surgery using a bronze needle to push the clouded lens away from the pupil, and trepanation – drilling holes in the skull to relieve pressure from head injuries. His instructions for amputation include detailed steps for bone-sawing and wound cauterization using hot irons to prevent bleeding.

-> Discover more about daily life and health practices in our [Daily Life and Routines]

Herbal Medicine and Local Resources

The fertile landscape around Gerasa provided numerous medicinal plants documented by ancient sources. The territory of Gerasa included fertile agricultural land along the Chrysorrhoas River, which would have supported cultivation of medicinal herbs and provided access to naturally occurring therapeutic plants.

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Books 20-25) provides extensive documentation of plant-based remedies that would have been available to Gerasene practitioners. Some of his everyday cures that would seem strange today include mouse droppings mixed with honey for earaches, powdered deer antler in wine for stomach ailments, and goose fat applied to wounds to prevent infection. More palatable treatments included willow bark tea for fever (containing what we now know as salicin, related to aspirin) and honey mixed with crushed garlic for respiratory infections.

- Olive oil and wine, both produced locally according to archaeological evidence of olive presses, served as bases for many treatments

- Wild herbs from the surrounding hills provided ingredients for digestive and respiratory ailments

- The springs that supplied Gerasa’s sophisticated water system were considered to have therapeutic properties

Columella (4-70 AD), in De Re Rustica (Book 12), describes household medicine and the cultivation of medicinal plants that would have been practiced in the agricultural territories surrounding Gerasa. His work details how Roman families maintained their own medical supplies and treated common ailments using locally available plants.

Mental Illness and Possession

The understanding of mental illness in Gerasa reflected the complex intersection of medical, religious, and cultural beliefs of the period. The Gospel accounts of the demoniac in the territory of the Gerasenes (Matthew 8, Mark 5, Luke 8) provide crucial insight into the condition of cast-outs who were perceived as either mentally deranged or as demon possessed depending on their belief.

Celsus (De Medicina, Book 3) distinguished between different types of mental afflictions. He describes insania (madness) as having various forms, some considered medical conditions treatable through diet and physical therapy, others attributed to supernatural causes. His medical treatments for melancholia included cold baths, a diet rich in vegetables and light wines, and bloodletting from the arms. For violent madness, he recommended restraining the patient with soft leather bonds and administering hellebore (a toxic plant) in carefully measured doses. In Gerasa, as throughout the Roman world, the interpretation often depended on the specific symptoms and circumstances:

- Gradual onset conditions with clear physical symptoms were more likely to receive medical treatment

- Sudden, violent behavior accompanied by supernatural manifestations was attributed to demonic possession

- Chronic conditions might be seen as divine punishment or hereditary weakness

Josephus (37-100 AD), our contemporary Jewish historian, in Jewish Antiquities (Book 8), describes Jewish approaches to treating possession through exorcism and notes that such practices were recognized throughout the Roman world. The presence of a Jewish community in Gerasa, evidenced by archaeological finds including fragments of Jewish purity vessels, meant that multiple approaches to mental illness coexisted within the city.

-> Explore the religious context of healing in our [Religious Landscape of Gerasa]

Sacred Healing and Temple Medicine

The sanctuary complexes of Zeus Olympios and Artemis in Gerasa likely served healing functions beyond their primary religious purposes. Throughout the Greek and Roman world, temples functioned as centers for sacred healing, where priests performed rituals and administered treatments.

The cult of Artemis, prominently worshipped in Gerasa as evidenced by the massive temple complex, was specifically associated with childbirth and women’s health. Sacred healing at such sites often involved:

- Purification rituals using water from sacred springs, followed by drinking the blessed water for internal cleansing

- Sacred offerings of small terracotta body parts representing the afflicted area, requesting divine intervention

- Temple incubation, where patients slept overnight in the sacred precincts hoping to receive healing dreams from the goddess

- Priestly interpretation of symptoms combined with prescribed offerings of honey cakes, wine, or small animals such as doves, young lambs, or roosters

- Integration of medical and religious approaches, such as applying medicinal herbs like mint, rosemary, or thyme blessed by temple priests

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 28) documents numerous healing practices associated with religious sites and notes the widespread belief in the therapeutic power of sacred spaces and rituals.

Public Health and Urban Infrastructure

Roman emphasis on public health infrastructure significantly impacted daily life in Gerasa. The city’s sophisticated water management system, including aqueducts, cisterns, and public fountains, reflected understanding of the connection between clean water and health.

The document evidence shows that Gerasa had an elaborate water supply system with springs located at Suf, approximately 7 kilometers northwest of the city. This system provided residents with access to clean water, crucial for preventing waterborne diseases that were common concerns in ancient urban centers.

Public bath complexes served multiple health functions:

- Maintaining personal hygiene

- Providing spaces for therapeutic treatments

- Offering opportunities for social interaction and mental well-being

- Serving as centers for minor medical consultations

Professional Organization and Guild Systems

While the Roman empire widely utilized professional associations called collegia for organizing craftsmen and service providers, the specific evidence for such organizations in Gerasa or the broader Decapolis region remains limited. The general Roman practice, as documented by Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 35) and evidenced throughout the empire, included medical practitioners organizing into professional associations.

These collegia typically served to:

- Regulate professional standards and training

- Provide mutual support during illness or economic hardship

- Maintain burial funds for deceased members

- Negotiate with local authorities regarding professional privileges

However, unlike major centers such as Rome or Ostia where extensive epigraphic evidence documents such associations, the current archaeological record from Gerasa does not provide specific evidence for medical collegia, though their existence would align with standard Roman municipal organization.

Emergency Medical Care and Trauma Treatment

The Roman military presence and active trade routes meant that Gerasa’s medical practitioners needed skills in treating injuries and trauma. Celsus (De Medicina, Books 5-7) provides detailed descriptions of surgical procedures for wounds, fractures, and other injuries that would have been essential knowledge for any practitioner serving a diverse urban population.

The presence of blacksmiths and metalworkers in Gerasa meant regular treatment of burns, cuts, and other workshop injuries. Common emergency treatments included:

- Cauterization for serious bleeding using heated bronze or iron instruments, often shaped like small spoons or rods

- Setting and splinting of fractures using wooden supports bound with linen strips soaked in egg whites, which dried to form a rigid cast

- Treatment of burns with a mixture of olive oil, vinegar, and crushed rose petals, applied under clean linen bandages

- Wound cleaning using wine (the alcohol content serving as an antiseptic) followed by application of spider webs, which were believed to promote clotting

-> Learn about the crafts that required medical attention in our [Metallurgy and Blacksmithing]

Women’s Health and Childbirth

Women’s health in Gerasa operated within traditional Roman frameworks but incorporated local customs and practices. Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 28) documents numerous remedies specifically for women’s conditions, many of which would have been known to midwives and female healers in provincial cities. For example, he recommends what would be considered today as a superstitious practice to wear an amulet containing a hyena’s eye during childbirth to ease labor pains. In the same vein, he also recommends what would now be considered folk remedies, such as applying a mixture of crushed snails and wine to the lower abdomen to treat monthly discomfort. More practical treatments included fennel tea to increase milk production in nursing mothers and the use of soft wool soaked in olive oil as absorbent padding during menstruation.

The prominence of Artemis worship in Gerasa reflects the importance placed on women’s health, as this goddess was specifically associated with childbirth and protection of women. Local midwives would have combined practical medical knowledge with religious rituals to ensure safe deliveries.

Columella (De Re Rustica, Book 12) describes the role of the vilica (female overseer) in maintaining household medical supplies and treating women’s ailments, providing insight into how medical knowledge was transmitted among women in Roman households.

The Economics of Healthcare

Medical care in Gerasa operated within the broader economic framework of the Roman world. The presence of wealthy citizens capable of funding public works, as evidenced by numerous dedicatory inscriptions, suggests that some residents could afford extensive medical treatment, while others relied on family remedies and traditional healing methods.

The Roman system typically distinguished between:

- Elite physicians who served wealthy households and charged substantial fees

- Military medical staff who treated soldiers and veterans

- Local healers who provided basic medical services to the general population

- Household medical care administered by family members using traditional remedies

Conclusion

Medicine and healing in 1st-2nd century Gerasa represented a sophisticated blend of Greek medical theory, Roman practical application, and local traditional knowledge documented by contemporary sources such as Celsus, Pliny the Elder, and Columella. From trained physicians applying Hippocratic principles to household remedies prepared according to traditional formulations, healthcare reflected the city’s position as a cosmopolitan center within the Decapolis.

The approach to mental illness and possession, exemplified in the Gospel accounts, demonstrates the complex intersection of medical and religious understanding that characterized this period. Contemporary sources like Josephus provide insight into how Jewish, Greek, and Roman approaches to healing coexisted in cities like Gerasa.

This medical landscape forms an essential backdrop for stories set in Gerasa, where characters would have navigated these various approaches to health and healing as part of their daily lives, whether facing common ailments, traumatic injuries, or the mysterious afflictions that challenged both medical knowledge and spiritual understanding of the time.

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja

Leave a Reply