Note: This article synthesizes archaeological evidence from approximately 1-200 AD to provide a comprehensive overview of Gerasa’s architectural development during the early Roman period.

Monumental Ambition in Stone

The architecture of Gerasa during the first two centuries AD tells a story of civic ambition, religious devotion, and cultural synthesis. As the city grew in prosperity and importance within the Roman provincial system, its buildings became increasingly monumental and sophisticated, reflecting both local traditions and the broader architectural language of the Roman East.

The cityscape that emerged during this period was dominated by grand public structures built primarily of locally quarried limestone. These buildings followed Greco-Roman architectural principles while incorporating regional adaptations, resulting in a distinctive architectural character that set Gerasa apart from other cities of the Decapolis.

Religious Architecture: Divine Dwellings

The Sanctuary of Zeus Olympios

Among the most impressive structures in early Roman Gerasa was the Sanctuary of Zeus Olympios, which underwent multiple construction phases from the late Hellenistic period through the 2nd century AD. Located on a prominent hill overlooking the Oval Plaza, this sanctuary complex showcased sophisticated engineering solutions to accommodate both religious requirements and challenging topography.

The sanctuary consisted of two main terraces. The lower terrace, created during the early 1st century AD, featured a monumental propylon (gateway) with a colonnaded courtyard. The upper terrace, crowned by the temple itself, was approached via a monumental staircase that created a dramatic processional experience for worshippers. The temple was constructed in the peripteral form with eight columns across the façade (octostyle), showcasing the grandeur expected of a temple dedicated to the supreme Olympian deity.

Archaeological investigations have revealed that the temple’s construction involved innovative engineering techniques, particularly in the vaulted structures supporting the terraces. An inscription found at the site identifies Diodoros, son of Zebeidos, as the architect of the vaulted corridors—a rare instance where we know the name of the individual responsible for a specific architectural achievement in the city.

One particularly remarkable architectural element discovered in the sanctuary is a suspended keystone, part of a vaulted entrance. This exceptional decorative and technical feature, found during excavations in 2014, bears an inscription honoring a certain Demetrios as the founder of the portico. The technique used to create this suspended keystone represents a rare example of architectural innovation, showcasing the high level of technical expertise available to Gerasa’s builders in the early 1st century AD.

The Temple of Artemis

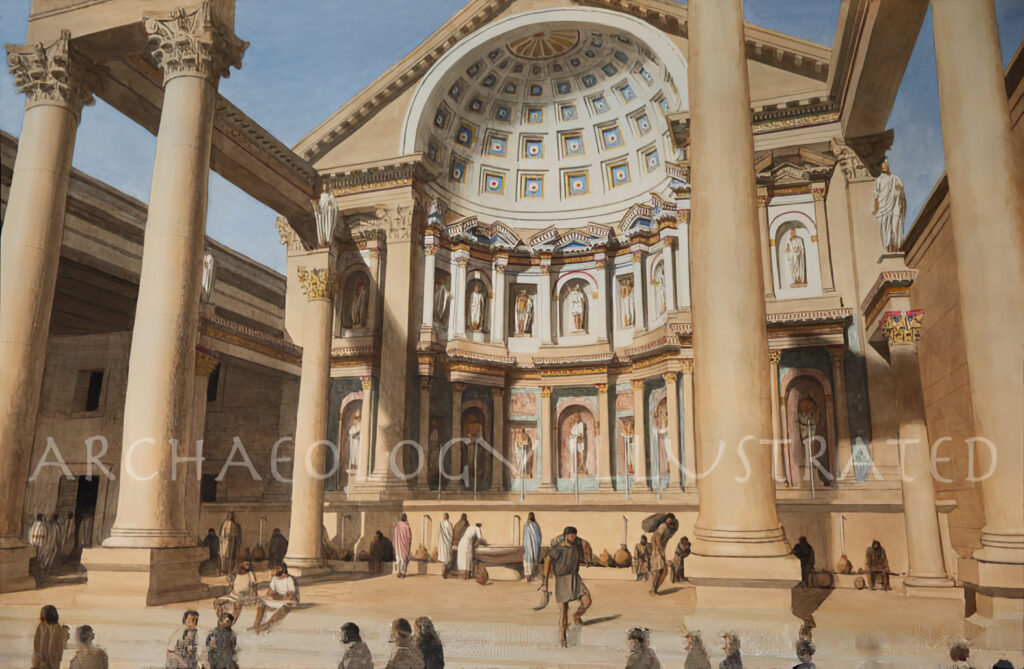

By the mid-2nd century AD, Gerasa’s skyline was dominated by the massive Temple of Artemis, which surpassed even the Zeus complex in scale and grandeur. The temple stood at the center of a vast sacred precinct that ascended in a series of terraces from the Cardo Maximus. The architectural ensemble included a monumental gateway accessed from the Cardo, a broad staircase leading to a spacious plaza, and finally the temple itself, raised on a high podium.

The temple was designed in the hexastyle peripteral form, with six columns across the front and eleven along each side. These massive columns, topped with elaborately carved Corinthian capitals, supported an entablature adorned with intricate decorative elements. The sanctuary’s design created a dramatic visual experience, with the temple becoming progressively more visible as visitors ascended through the complex, culminating in the impressive façade that dominated the sacred precinct.

The Temple of Artemis represented not only religious devotion but also civic pride and identity. As the patron deity of Gerasa, Artemis received particular architectural attention, and her temple served as a powerful statement of the city’s importance within the wider region. The temple’s design incorporated elements from the imperial architectural vocabulary, connecting Gerasa to the broader cultural framework of the Roman Empire while maintaining distinctive local characteristics.

Public Buildings: The Stage of Civic Life

Theaters and Odeion

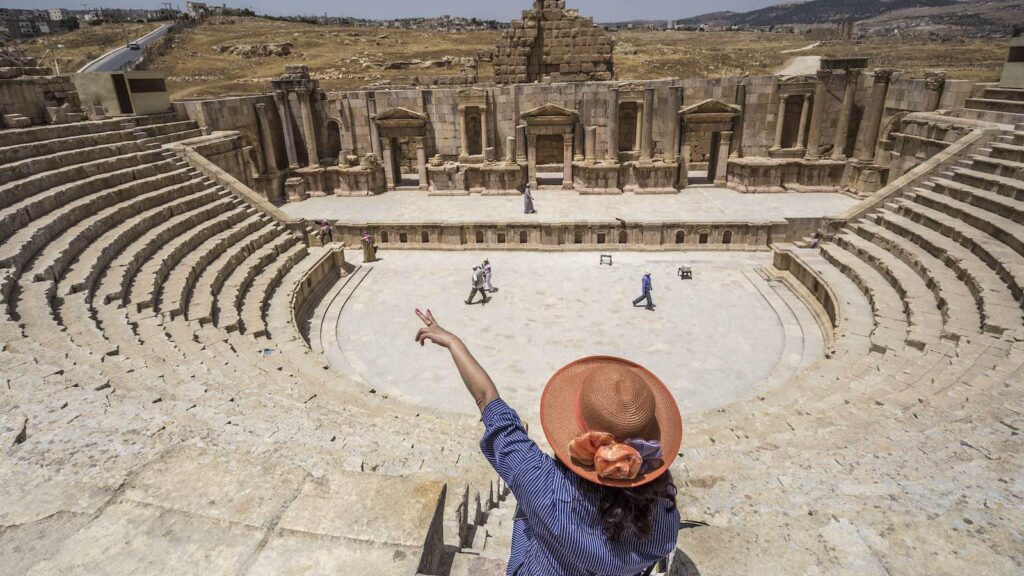

Roman Gerasa boasted two theaters that served different but complementary functions within civic life. The South Theater, constructed in the late 1st century AD, was the larger of the two, with a capacity of approximately 3,000 spectators. Its design followed the typical Roman theater layout, with a semicircular cavea (seating area) divided into horizontal sections by circulation passageways and vertical stairways. The scaenae frons (stage building) featured an elaborately decorated two-story façade with columns, niches, and entablatures—creating an impressive architectural backdrop for performances.

The North Theater, slightly smaller and dating to the early 2nd century AD, likely functioned as a bouleuterion or odeon—a combined council chamber and performance space. Archaeological evidence suggests that the front rows were equipped with stone benches with backs rather than the simple stone seats found in the main theater, indicating the privileged seating area for civic officials. Inscriptions discovered on the seats of this structure mention different tribes of the city, suggesting that political representation in Gerasa was organized along tribal lines, with designated seating for tribal representatives.

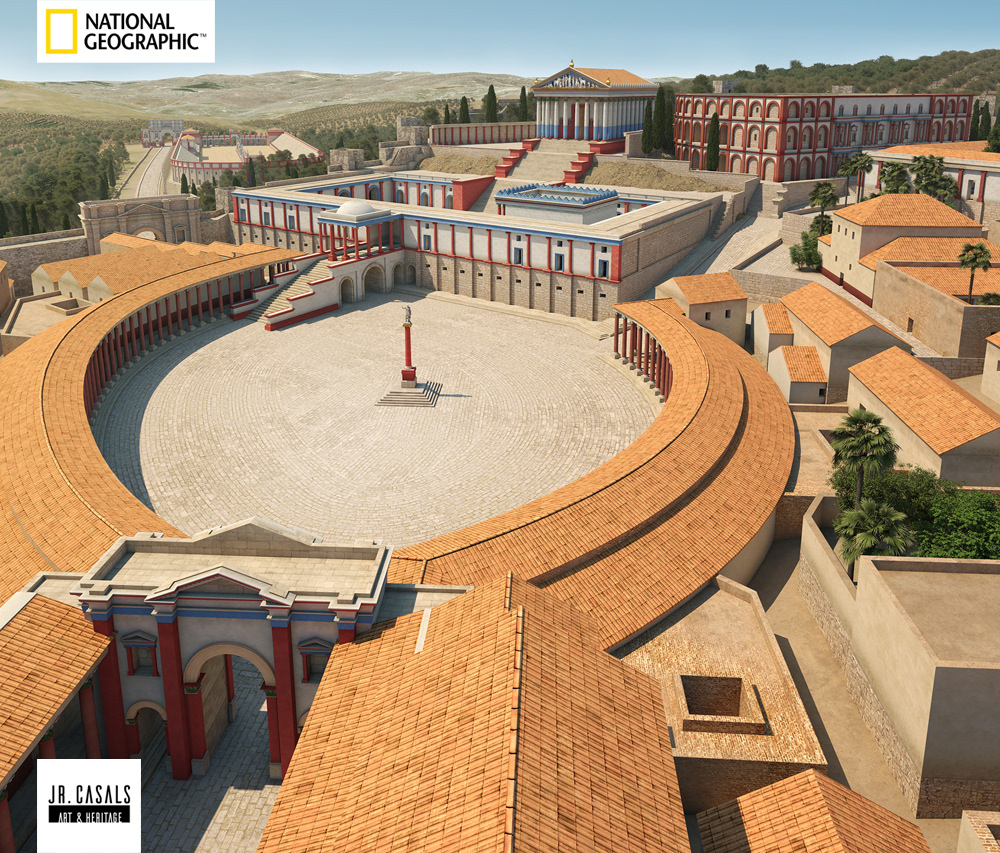

The Oval Plaza and Public Squares

One of Gerasa’s most distinctive architectural features is the Oval Plaza (Forum), an elliptical public space that served as a transitional element between the Cardo Maximus and the Sanctuary of Zeus. Paved with limestone slabs and surrounded by a colonnade of Ionic columns, this unusual plaza deviated from the typical rectangular forum found in most Roman cities.

The plaza’s design demonstrated the architects’ creative response to the topographical and urban challenges of connecting the main street with the sanctuary on the hill. Its oval shape facilitated the smooth flow of traffic and processions between these important urban elements while creating a dramatic public space for gatherings and ceremonies. The careful integration of this plaza into the urban fabric exemplifies the sophistication of Gerasa’s urban planners and architects.

Nymphaeum and Fountains

Water display was an essential element of Roman urban aesthetics, and Gerasa’s monumental Nymphaeum, constructed in the 2nd century AD, exemplified this tradition. Located along the Cardo Maximus, this elaborately decorated fountain building featured a semicircular façade with niches, columns, and an intricate water distribution system that created cascading effects.

The Nymphaeum’s design combined practical water distribution with theatrical display, providing both a source of drinking water for passersby and an impressive architectural statement. Its decoration included marble veneer, sculptures, and possibly mosaic elements, all enhancing the sensory experience of this public monument. The building’s location at a major intersection of the city guaranteed its visibility and reinforced the association between water abundance and civic prosperity.

Baths and Bathing Complexes

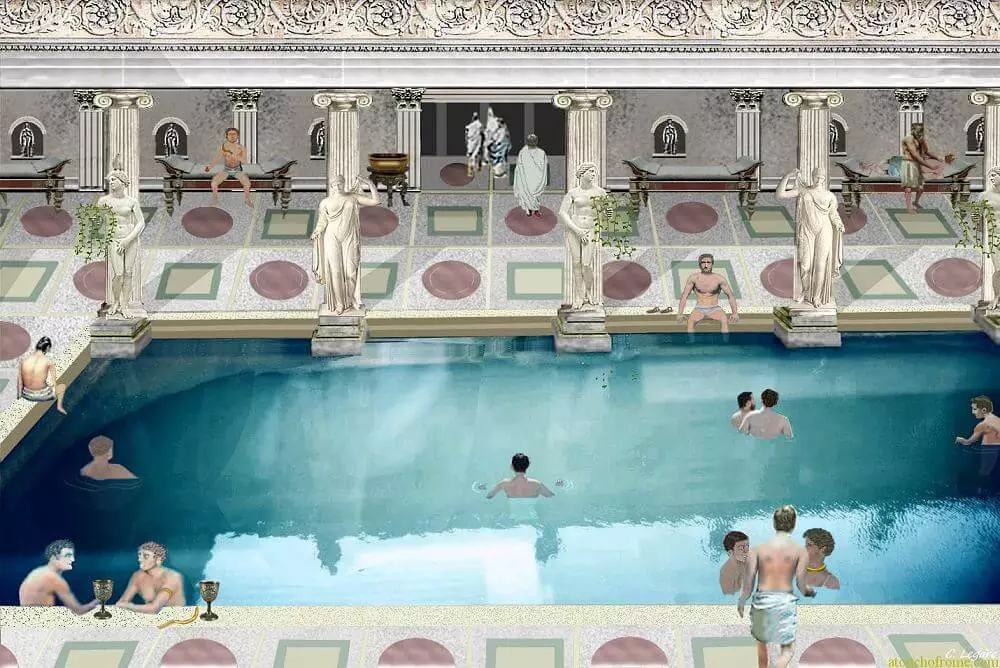

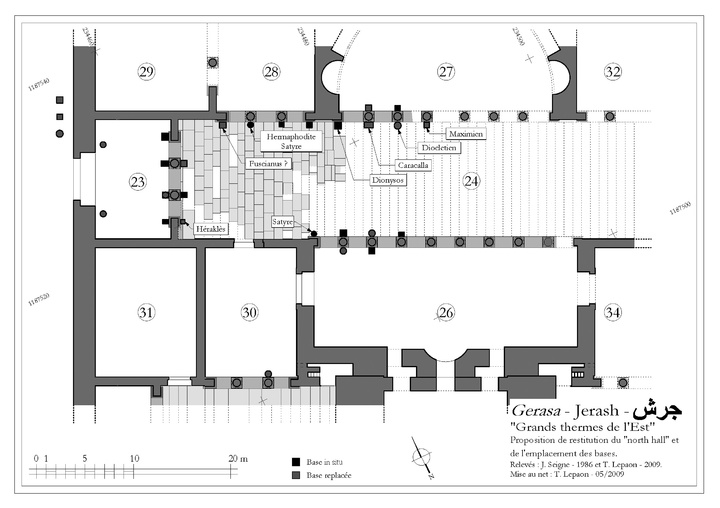

Roman bathing culture was represented in Gerasa by several bath complexes, most notably the Great Eastern Baths, constructed in the late 2nd century AD. This massive complex featured the typical sequence of bathing rooms (frigidarium, tepidarium, caldarium) arranged in a symmetrical plan, with additional spaces for exercise, socializing, and other activities.

The baths’ architecture showcased sophisticated engineering solutions for water management and heating, including hypocaust systems beneath the floors and within the walls of heated rooms. Excavations have revealed evidence of elaborate decoration, including marble statuary, colored marble wall veneers, and possibly mosaic floors. The Great Eastern Baths, like their counterparts throughout the Roman world, served as important spaces for social interaction and cultural exchange, as well as personal hygiene.

Recent archaeological work at the Great Eastern Baths has uncovered evidence of a “North Hall complex,” which appears to have been a monumental space connected to the bathing facility. This hall contained numerous statue bases and fragments of marble sculptures, suggesting it functioned as an impressive gallery space showcasing the city’s artistic wealth.

Private Architecture: Homes and Workshops

While Gerasa’s public monuments have received the most archaeological attention, evidence of private architecture provides glimpses into the daily living environments of the city’s inhabitants across different social strata.

Elite Residences

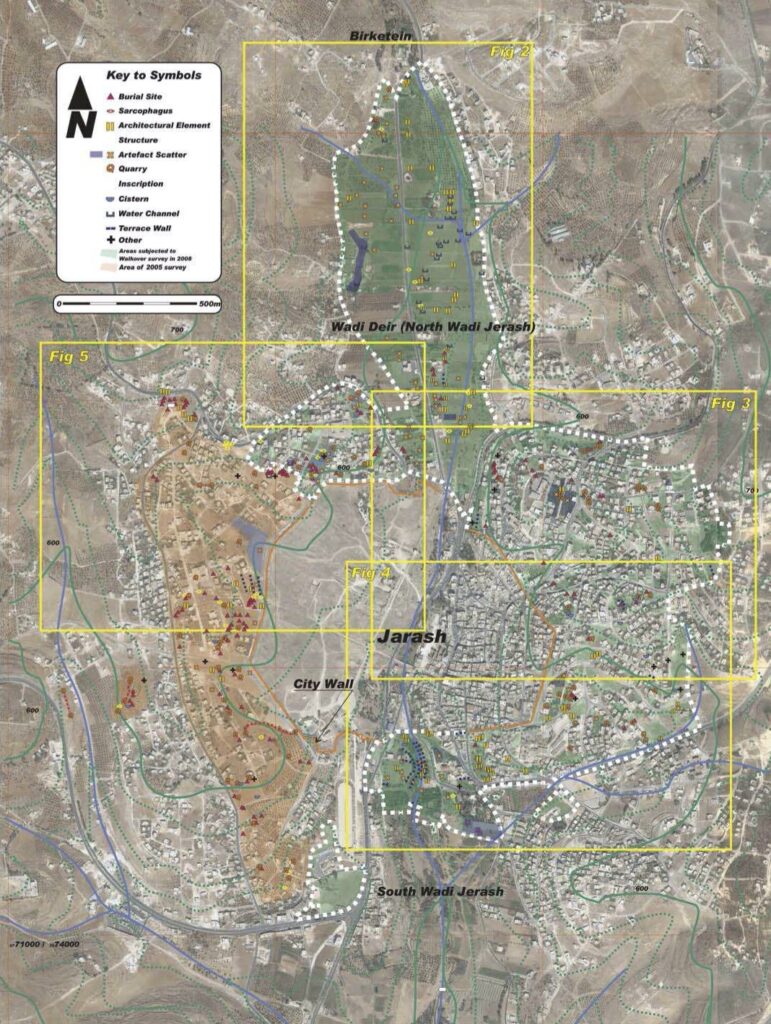

The homes of Gerasa’s wealthy citizens likely followed Greco-Roman residential models adapted to local conditions. Archaeological evidence from the Northwest Quarter and other areas suggests that elite homes featured peristyle courtyards with columns surrounding central open spaces, providing light, air circulation, and private outdoor areas within the house. These residences were often constructed on terraces on the hillsides, particularly in the western sectors of the city, taking advantage of the views and the natural topography.

Decoration in these homes included limestone and marble architectural elements, wall paintings, and occasionally mosaic floors in the most important rooms. The overall design emphasized privacy from the street, with major rooms facing inward toward courtyards rather than outward toward public spaces—a characteristic feature of Mediterranean domestic architecture.

Middle and Lower-Class Housing

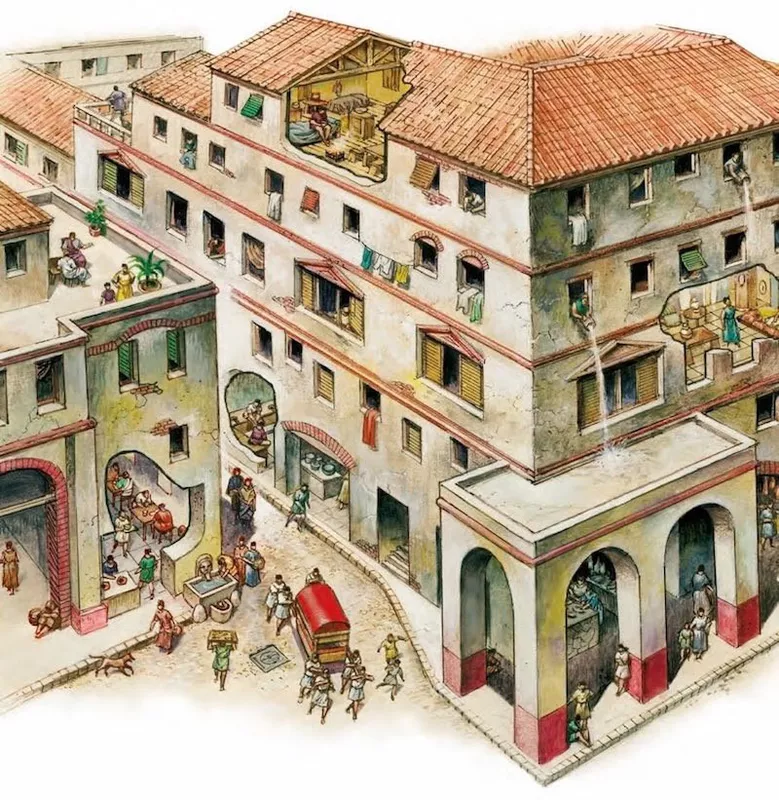

For the majority of Gerasa’s inhabitants, housing was likely more modest in scale and decoration but still followed similar organizational principles. Middle-class homes may have featured smaller courtyards or light wells, with fewer rooms arranged around these central spaces. Construction techniques would have been similar to those used in elite homes, though with less expensive materials and simpler decoration.

The lower classes likely occupied multi-family structures or simple houses with fewer rooms and minimal decoration. Archaeological evidence for these structures is more limited, as they were often built with less durable materials and have not survived as well as the more substantial elite residences.

Commercial and Workshop Spaces

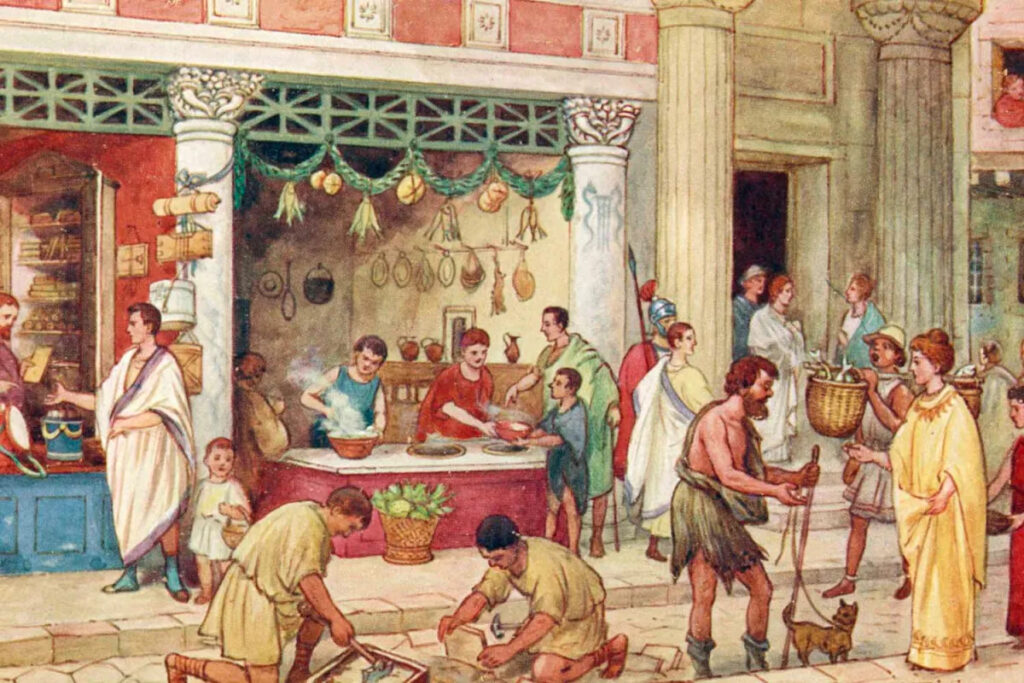

Shops and workshops occupied prominent locations along the main streets, particularly beneath the colonnaded porticoes of the Cardo Maximus. These commercial spaces typically consisted of single rooms opening directly onto the street, with wide doorways that could be closed with wooden shutters. Some merchants and artisans may have lived in rooms above or behind their shops, creating combined commercial-residential spaces typical of Roman urban environments.

Archaeological evidence suggests that certain industries were concentrated in specific areas of the city. Pottery production, metalworking, and other activities that required furnaces or produced noxious byproducts were likely located in peripheral areas or near the city walls to minimize fire risks and pollution in densely inhabited neighborhoods.

Construction Materials and Techniques

Stone: The Foundation of Gerasa’s Architecture

The primary building material throughout Gerasa was locally quarried limestone, which existed in several varieties with different properties. The soft, whitish limestone (known locally as “narri”) was easily worked and thus used extensively for most construction, while harder, more durable limestone varieties were reserved for elements requiring greater structural strength or aesthetic quality, such as column drums, architraves, and decorative elements.

Evidence of quarrying activity is visible throughout the area surrounding Gerasa, with numerous extraction sites identified in archaeological surveys. The proximity of these quarries to the city reduced transportation costs and facilitated the massive building programs undertaken during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

For particularly important buildings or decorative elements, imported materials supplemented local stone. Marble from Asia Minor and other eastern Mediterranean sources was used for sculpture, columns, and architectural decoration in major public buildings, especially in the Great Eastern Baths and the temples. These imported materials represented significant investments and underscored the wealth and cosmopolitan connections of the city.

Masonry and Construction Techniques

The masonry techniques employed in Gerasa reflected both local building traditions and broader Roman practices. Public buildings typically featured ashlar masonry, with carefully cut rectangular blocks laid in regular courses. The quality of stonework varied depending on the importance of the building and the visibility of the surface—façades and other prominent areas received more careful treatment than utilitarian or hidden sections.

Vaulted construction played a particularly important role in Gerasa’s architecture, as evidenced by the sophisticated vaulted corridors of the Zeus sanctuary. These structures employed both barrel and arched vaults, often constructed without centering (temporary wooden supports) through innovative techniques developed by local architects like Diodoros. The discovery of an inscribed suspended keystone from one of these vaults demonstrates the high level of technical expertise achieved by Gerasa’s builders.

For more modest structures, rubble and irregular stone construction was common, usually covered with plaster to create a more finished appearance. Foundations typically consisted of larger, roughly dressed stones set directly on bedrock where possible, providing stable support for the superstructures.

Architectural Decoration

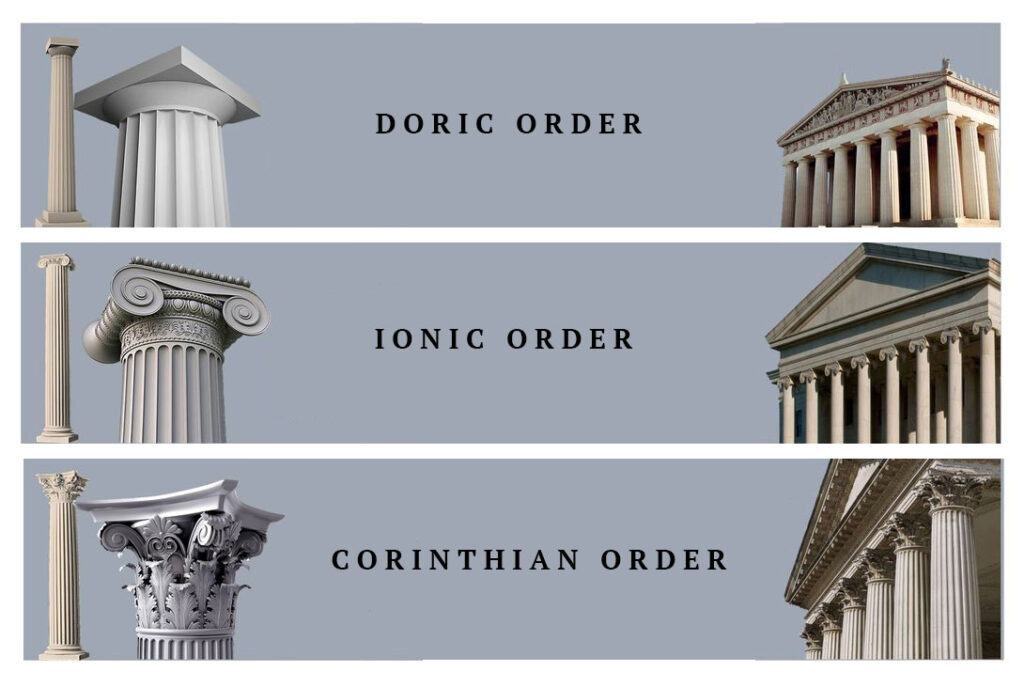

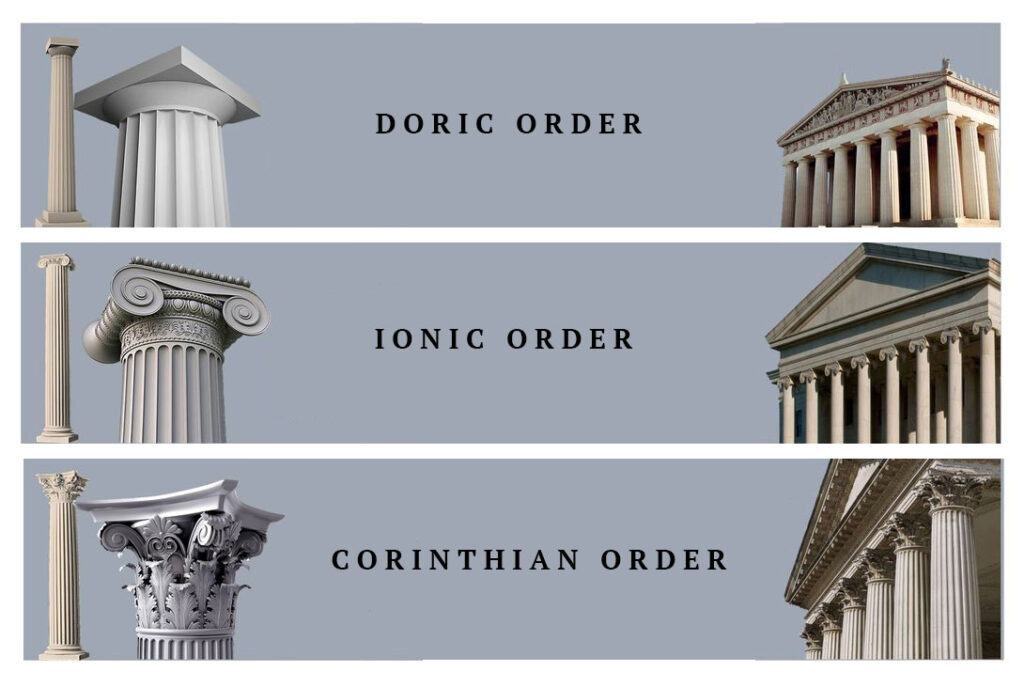

The decorative vocabulary of Gerasa’s buildings combined elements from the broader Greco-Roman tradition with regional preferences and innovations. Column capitals followed the standard classical orders—primarily Corinthian for major monuments, with Ionic and occasionally Doric elements in secondary structures. The execution of these capitals by local craftsmen introduced subtle variations and regional characteristics while maintaining the overall classical framework.

Wall surfaces in major public buildings were often covered with marble veneer or painted plaster, creating colorful interiors that contrasted with the relatively austere limestone exteriors. Archaeological evidence from the Great Eastern Baths includes fragments of colored marble panels imported from various quarries throughout the Mediterranean region, suggesting richly decorated interior spaces.

Sculptural decoration was integrated into architectural settings, particularly in the temples, theater façades, and the Nymphaeum. These sculptural programs combined religious imagery, imperial themes, and civic symbolism, reinforcing the buildings’ functions while demonstrating Gerasa’s participation in the broader visual culture of the Roman Empire.

Reuse and Adaptation

An important phenomenon in Gerasa’s architectural history is the reuse of architectural elements from older buildings in new construction, termed “spolia.” This practice, which became increasingly common in later periods, is already evident in the 1st-2nd centuries AD, suggesting a pragmatic approach to available materials alongside a possible desire to incorporate elements from earlier structures for their historical or symbolic value.

Archaeological investigations in the Northwest Quarter have documented cycles of construction, destruction, demolition, and reuse spanning many centuries. This pattern reflects the dynamic nature of urban development in Gerasa, with each generation adapting and transforming the built environment according to changing needs, resources, and cultural influences.

Engineering Achievements

Water Management Systems

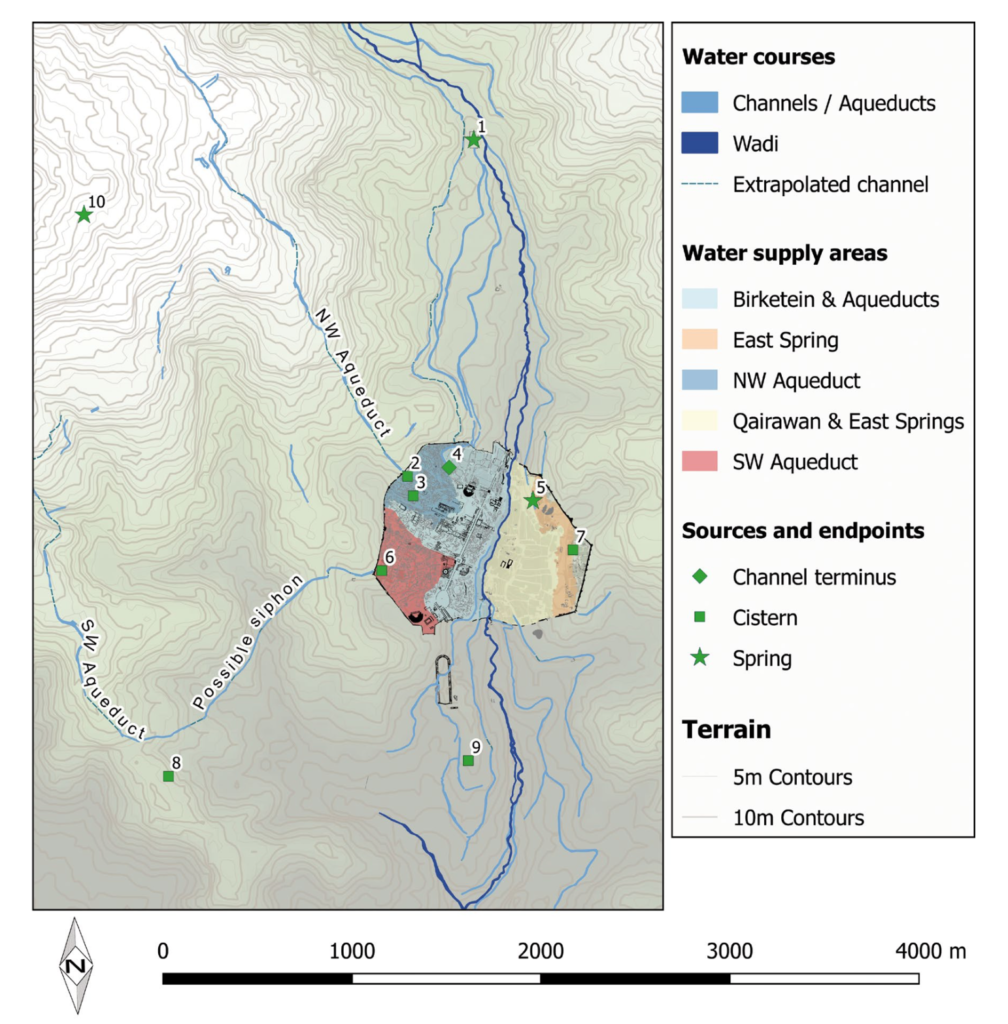

The architecture of water management represented some of Gerasa’s most impressive engineering achievements. The city’s location in a semi-arid environment with seasonal rainfall patterns necessitated sophisticated systems for water collection, storage, and distribution.

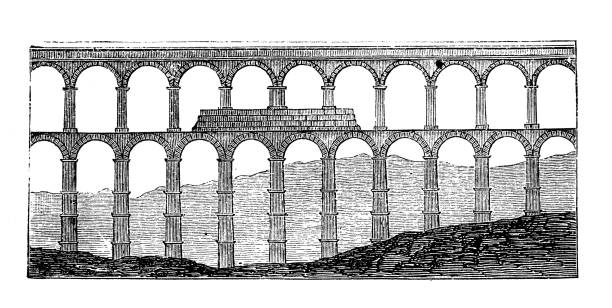

Aqueducts brought water from springs at Suf, approximately 7km northwest of the city, through carefully engineered channels that maintained the necessary gradient for gravity flow. Within the city, water was distributed through pipes made of ceramic, stone, or lead, feeding public fountains, baths, and private residences.

Cisterns cut into the bedrock provided storage capacity to maintain water supplies during dry periods. These engineering works represented major investments in infrastructure that underpinned the city’s growth and prosperity during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

Building on Challenging Terrain

Gerasa’s location on hilly terrain presented challenges that inspired creative architectural solutions. The city’s major sanctuaries, in particular, demonstrate the builders’ ability to transform topographical constraints into dramatic architectural opportunities.

The Sanctuary of Zeus utilized a series of terraces and vaulted substructures to create level platforms on the hillside, while the Temple of Artemis employed a high podium and monumental stairways to establish its dominant position within the urban landscape. These solutions not only addressed practical engineering requirements but also enhanced the experiential quality of these sacred spaces, creating impressive processional routes that heightened the visitor’s sense of approaching the divine.

Conclusion

The architectural features and building styles of Gerasa during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD reflect a city that was thoroughly engaged with the broader currents of Roman imperial architecture while maintaining distinctive local characteristics. From monumental temples and public buildings to private homes and infrastructure, Gerasa’s built environment embodied the city’s prosperity, cultural synthesis, and civic ambition.

The sophisticated engineering solutions, high-quality craftsmanship, and monumental scale of these structures speak to the skills of Gerasa’s architects and builders, as well as the resources available to the city during this period of economic flourishing. Through their architectural achievements, the people of Gerasa created an urban environment that not only served their practical, religious, and social needs but also proclaimed their city’s importance within the network of Roman provincial centers in the eastern Mediterranean.

Today, the remarkably preserved ruins of these structures provide an unparalleled window into the architectural ambitions and achievements of a prosperous provincial city during the height of the Roman Empire—a tangible legacy of stone that continues to inspire wonder and admiration two millennia after its creation.

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

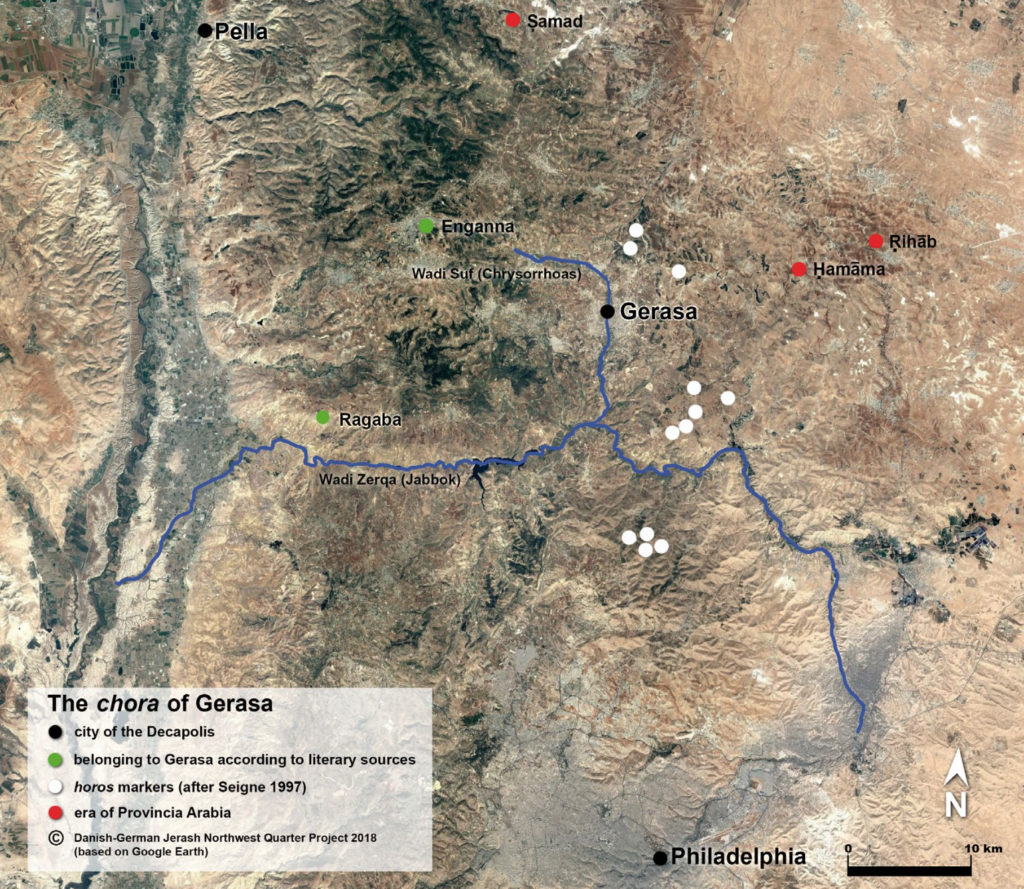

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja