Note: This article combines archaeological and historical evidence spanning from Gerasa’s early development through the 2nd century AD to present a comprehensive picture of the city’s geographical setting.

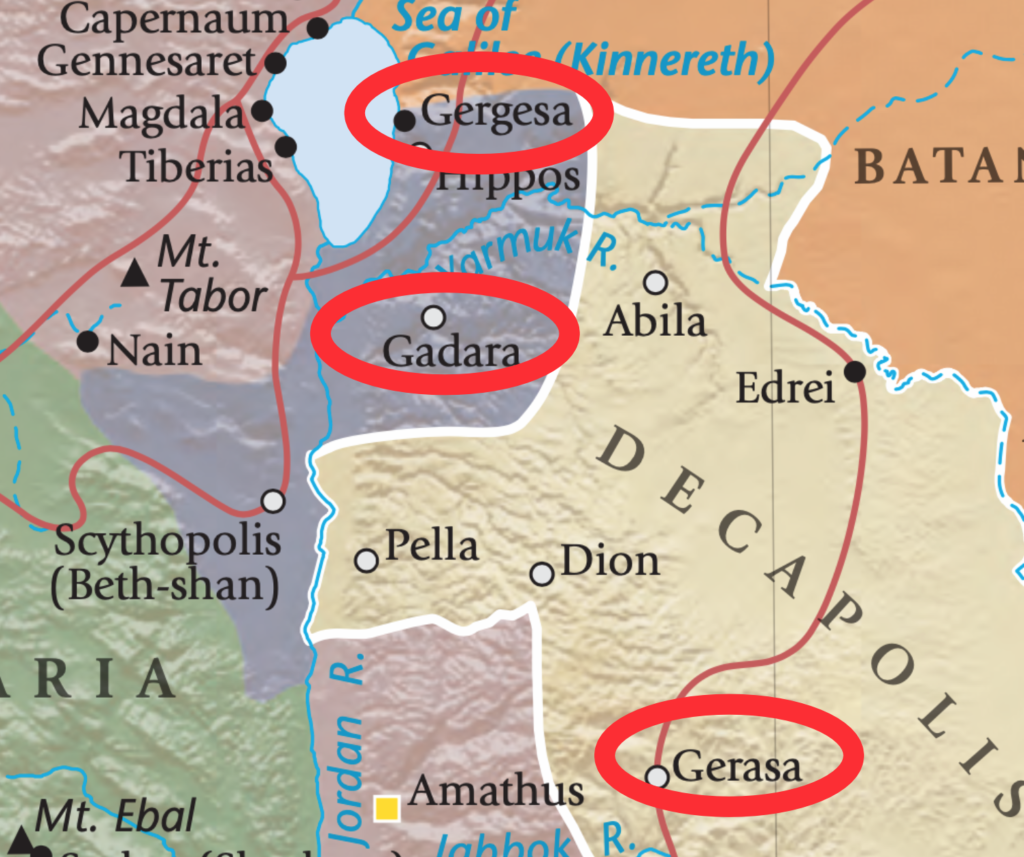

While the historian Josephus mentions Gerasa in his work “Wars of the Jews,” no archaeological evidence at the site supports his accounts. This may be due to confusion with Gergasa (modern Khersa) on the Sea of Galilee, where the biblical miracle of the swine took place according to the Gospels of Matthew 8, Mark 5, and Luke 8.

A turning point in Gerasa’s history came in 69 BC when Pompey conquered the Maccabean Kingdom of Palestine, ending their raids on the city. By keeping the Nabataeans to the south in check through the threat of military intervention, Pompey established a period of peace that allowed the Decapolis region to flourish.

Under the Roman Empire, Gerasa became known as “Antioch on the Chrysorroas.” While its exact founding date remains unknown, this name suggests the city was either established or refounded by one of two Seleucid kings: Antiochus III (223-187 BC) or Antiochus IV (175-163 BC). Though officially a Greek city-state, inscriptions reveal that most inhabitants were Semitic peoples who adopted Greek culture rather than ethnic Greeks. This is evidenced by families using both Semitic and Greek names interchangeably, a practice ethnic Greeks typically avoided. While the upper classes embraced Greek language, culture, and politics, the lower classes maintained their Aramaic language and traditional customs, creating a distinct cultural divide.

Gerasa experienced its greatest prosperity during the first three centuries AD, with most of its monuments being constructed during the latter half of the 2nd century and into the 3rd century AD. Despite its commercial success and network of roads connecting it to other prosperous towns, the city remained politically neutral. Its legacy lives on primarily through its magnificent ruins and possibly through the mathematical writings of Nichomachus, if he was indeed a citizen.

The city’s vitality was sustained by abundant water sources, including springs located two kilometers above the city and others within its walls. The valley’s river flows from north to south, eventually joining the Zarqa River (ancient Jabbok). The stream banks below the city supported groves of fruit and walnut trees, along with stands of poplars, creating a green oasis in the surrounding arid landscape.

A deep valley divides Gerasa into eastern and western halves, with the Chrysorroas river flowing through its center, contained by impressive retaining walls. While only two bridges – the southern bridge and the viaduct – are confirmed to have connected the city’s halves, the presence of the North Tetrapylon suggests there may have been a third crossing point, though no archaeological evidence has yet confirmed this theory.

The city’s water supply system deserves special mention. Water was brought in from springs located two kilometers above the city, as well as from sources within the walls. The valley was known as “Chrysorroas” – the stream of gold – either referring to the wealth it brought through agriculture or its appearance during harvest season. Below the city, the river valley supports lush gardens planted with fruit trees, walnuts, and poplars.

Understanding the geographical context of Gerasa helps us appreciate how deeply the city’s development was rooted in its natural setting. As we explore other aspects of life in this remarkable ancient city, we’ll continue to see how its geography shaped everything from its economic activities to its religious practices, from its architecture to the daily lives of its inhabitants.

Disclaimer:

All images used on this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja