Previous: “Daily Life and Routines”

Note: This article presents material culture from Gerasa spanning 1-200 AD, drawing together archaeological evidence from different periods to illustrate the rich domestic life of this Decapolis city.

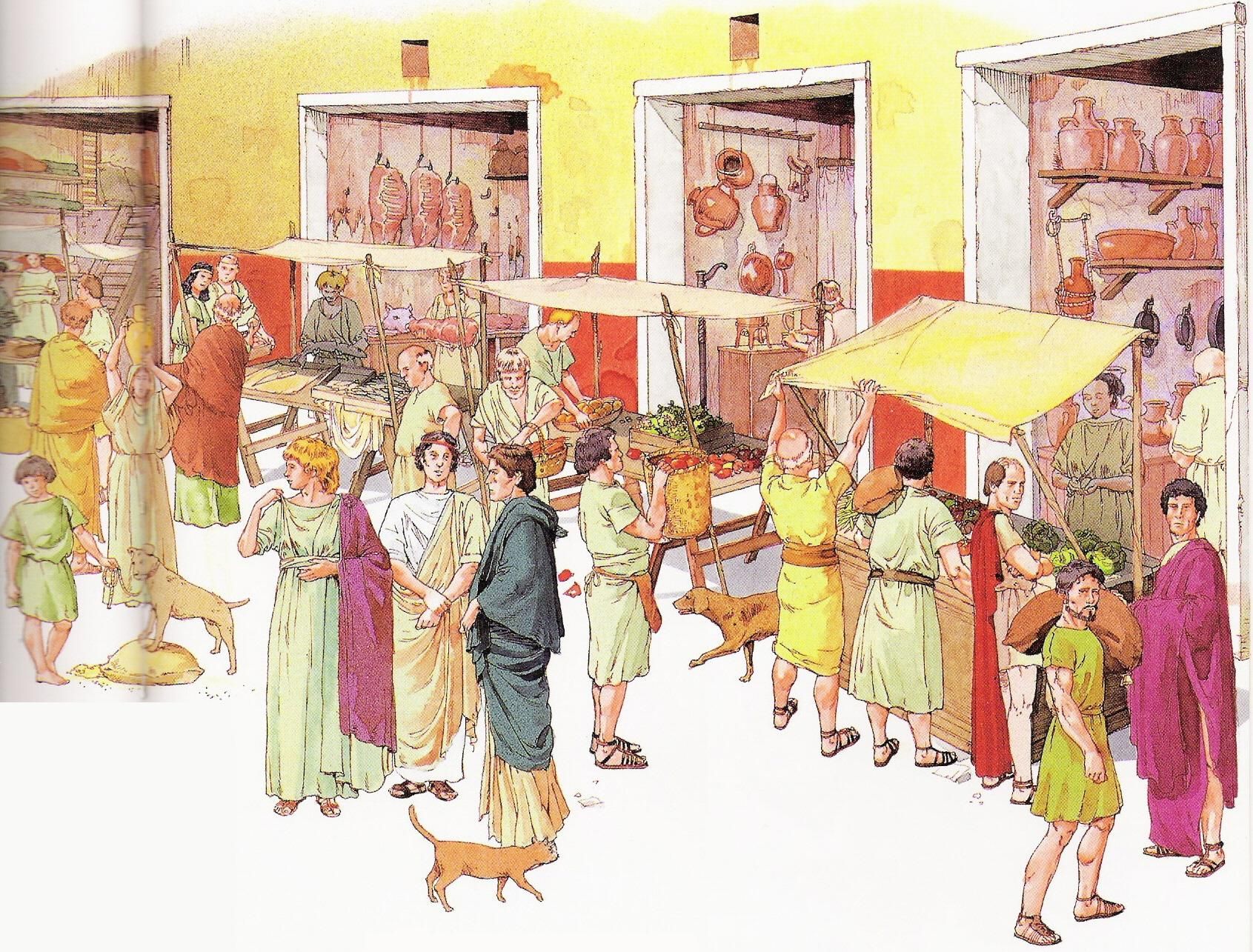

The material possessions of ancient Gerasa during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD tell a story of growing prosperity and cultural exchange. From humble cooking vessels to architectural stonework, the objects that filled homes and public spaces reveal how residents lived and worked in this developing Roman provincial city.

Pottery: The Foundation of Daily Life

Local Ceramic Production

Gerasa’s ceramic industry formed the backbone of domestic life during the Roman period. Archaeological excavations have revealed that most pottery in Gerasa was locally produced, with potters working primarily with local clay sources to create vessels for cooking, storage, and serving.

Evidence from the Northwest Quarter indicates that local ceramic production was important to the city’s economy during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The continuity of pottery-making traditions reflects both practical necessity and the maintenance of regional craftsmanship skills within the growing urban community.

Local potters created a wide range of vessel types to meet the diverse needs of Gerasa’s inhabitants. This domestic ceramic production demonstrates the city’s ability to supply essential household goods for its expanding population during this period of urban development.

-> Discover the workshops where these vessels were made in our [Walking Through Ancient Gerasa: A Monument-by-Monument Guide]

Cooking and Storage Vessels

The kitchens of Roman-period Gerasa contained various ceramic vessels designed for specific purposes. Large storage jars held oil, wine, and grain, while medium-sized pots served for cooking stews and boiling water. Smaller vessels included bowls for mixing, cups for drinking, and specialized forms for particular foods.

Different pot shapes reflected sophisticated cooking practices. Some vessels were designed for slow braising, others for quick boiling, and specialized forms for baking bread or preparing dishes requiring specific heat distribution. This variety indicates the culinary sophistication of Gerasa’s inhabitants during the Roman period.

The abundance of cooking and storage vessels found in archaeological contexts demonstrates the domestic prosperity that characterized Gerasa during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, when the city was establishing itself as an important center within the Decapolis.

-> Learn about the dining customs that used these vessels in our [Daily Life and Routines]

Stone and Construction Materials

Building with Local Resources

Local limestone was the primary building material in Gerasa during the Roman period. The soft whitish limestone found in the region provided an excellent medium for both structural construction and decorative carving, forming the foundation of the city’s architectural development.

Archaeological evidence shows that Roman-period constructions utilized this local stone extensively. The availability of high-quality limestone allowed builders to create both functional structures and decorative elements that reflected the city’s growing prosperity and cultural ambitions.

Water infrastructure represented a particularly important aspect of Roman-period construction. The sophisticated water management systems required specialized stonework and engineering, demonstrating the adoption of Roman building techniques adapted to local conditions and materials.

-> Explore the construction techniques in our [Urban Layout of Gerasa (1-200 AD)]

Architectural Elements

Column bases, capitals, and architectural decoration found in excavations represent Roman architectural styles adapted for local use. Standard types and forms of Roman decoration appear alongside regional characteristics, showing how Gerasa’s builders incorporated imperial architectural traditions while maintaining local craftsmanship.

The sanctuary complexes of Zeus and Artemis, active during our period, required substantial stonework and architectural decoration. These major religious centers would have showcased the finest architectural craftsmanship available in the city during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

Stone carving and architectural decoration during this period reflected both practical building needs and aesthetic aspirations. The quality of stonework found in Roman-period contexts indicates the presence of skilled craftspeople capable of creating sophisticated architectural elements.

Tools and Implements

Metalwork Evidence

Archaeological excavations have uncovered evidence of metalworking in Roman-period Gerasa. Iron tools served various trades and domestic purposes, while bronze and copper alloy objects functioned both as practical implements and decorative items.

Small finds from Roman contexts include needles for sewing, knives for food preparation, and specialized tools for various crafts. These objects reveal the diverse skills and activities of Gerasa’s inhabitants, from textile production to food processing to metalworking.

The presence of quality metal implements suggests social stratification in access to well-made tools. Wealthy households likely possessed finely crafted implements, while working families used simpler, locally produced tools appropriate to their means and occupations.

-> Learn about the craftspeople who made these tools in our [Economic Life in Gerasa]

Evidence of Trade and Prosperity

Regional Connections

Gerasa’s strategic position within the Decapolis facilitated trade connections with other centers during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The city’s growing prosperity during this period indicates successful participation in regional economic networks.

While most everyday pottery was locally produced, the city’s wealth would have allowed access to imported goods and luxury items. Such trade connections were essential for a city seeking to establish itself as an important regional center.

The variety of materials and techniques found in Roman-period contexts reflects cultural exchange between Gerasa and other centers. Local craftspeople learned from broader traditions while developing their own regional specialties.

Indicators of Wealth

The scale and quality of building projects during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD indicate significant wealth within the community. Major temple construction, water infrastructure, and public buildings required substantial resources and skilled labor.

Private households also show evidence of prosperity through the quality of domestic implements and pottery found in archaeological contexts. The range of vessel types and tool quality suggests a stratified society with significant wealth concentrated among the upper classes.

Investment in public infrastructure, particularly water management and religious buildings, demonstrates community wealth and civic pride during this formative period of Roman rule.

Archaeological Context and Evidence

Excavation Insights

Modern archaeological work has provided crucial insights into the material culture of Roman-period Gerasa. Systematic excavation has uncovered artifacts that illuminate daily life during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, though interpretation requires careful attention to chronological context.

The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project and other excavations have documented material remains from this period. However, distinguishing Roman-period contexts from later reuse requires careful stratigraphic analysis and chronological assessment.

Archaeological evidence from securely dated Roman contexts provides the most reliable information about material culture during our period. Such evidence forms the foundation for understanding how Gerasa’s inhabitants lived and worked during this crucial phase of urban development.

Material Preservation

Stone and ceramic objects survive well in Gerasa’s archaeological record, providing substantial evidence for material culture during the Roman period. These durable materials offer the best insights into daily life, construction practices, and economic activities.

Organic materials like wood, textiles, and leather rarely preserve, limiting our understanding of the full range of material culture. This preservation bias means our knowledge focuses primarily on stone, ceramic, and metal objects that could survive centuries of burial.

The exceptional preservation at Gerasa, combined with systematic excavation, continues to provide new insights into Roman-period material culture. Each discovery adds to our understanding of how this Decapolis city developed during the early centuries of Roman rule.

-> See how these objects fit into the broader regional context in our [The Decapolis: Ten Semi Autonomous Cities in Rome’s Shadow]

Conclusion

The material culture of Gerasa during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD reveals a community successfully adapting to Roman rule while maintaining local traditions. Pottery production, stonework, and metalworking demonstrate both practical competence and growing prosperity.

Archaeological evidence shows a society investing in infrastructure, religious buildings, and domestic comfort during this period. Local production capabilities combined with regional trade connections to create a material culture that served both daily needs and social aspirations.

The objects that filled Roman-period Gerasa reflect a population building a prosperous urban center within the broader framework of Roman provincial administration. From cooking pots to architectural stones, these material remains document the foundation period of what would become one of the Decapolis’s most successful cities.

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja

Leave a Reply