Previous: “Architectural Features and Building Styles”

Note: This article presents historical elements from Gerasa’s development between the 1st-2nd centuries AD, with some details drawn from structures and institutions that evolved throughout this period.

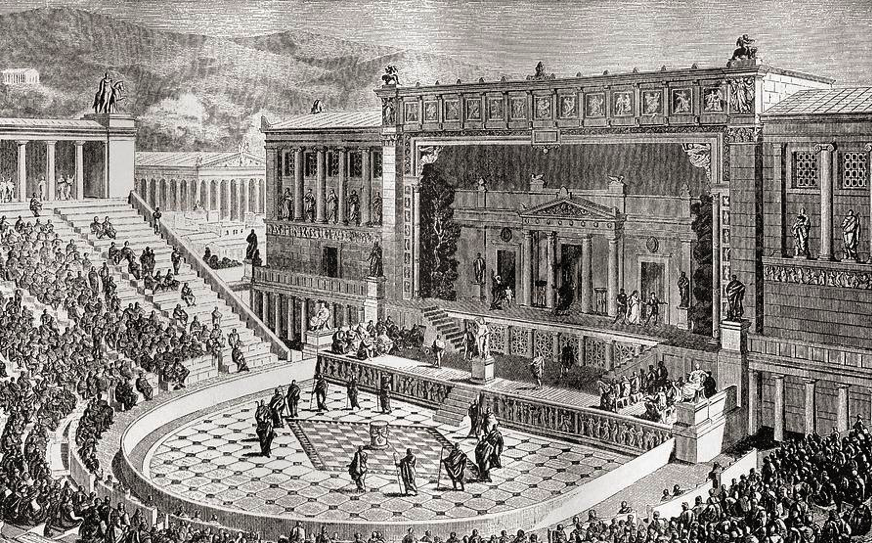

The magnificent colonnaded streets and monumental buildings of Gerasa reveal more than just architectural splendor—they reflect a sophisticated system of governance and civic organization. As a member of the prestigious Decapolis, Gerasa operated as a semi-autonomous city under Rome’s protective shadow, balancing local traditions with imperial oversight in ways that shaped every aspect of daily life.

Political Structure and Administrative Framework

Gerasa, known formally in some inscriptions as “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas” embodied the Greco-Roman polis model—a self-governing city with its own institutions and a defined territory. The city enjoyed remarkable continuity in its governance structures from the mid-1st century BC through the 2nd century AD, despite changing provincial affiliations.

When Pompey’s lieutenant Scaurus incorporated Gerasa into the Roman province of Syria in 63 BC, the city marked this event by establishing its own civic era. This date became the reference point for Gerasa’s chronology, appearing on public inscriptions and monuments—a testament to how the city viewed Roman “liberation” as the beginning of a new political identity.

The most significant administrative change occurred in 106 AD when Emperor Trajan annexed the Nabataean Kingdom and established the province of Arabia. Gerasa, previously part of the province of Syria, was transferred to this new province. Despite this provincial reorganization, the day-to-day governance of the city remained largely in local hands, with oversight from Roman officials.

-> Learn more about Gerasa’s place within the wider regional network in our article “The Decapolis: Ten Semi Autonomous Cities in Rome’s Shadow”

Civic Institutions and Local Governance

Archaeological and epigraphic evidence from Gerasa provides valuable insights into its civic administration. The city operated through several key institutions:

The Boule (City Council)

The boule or city council formed the cornerstone of local governance. Composed of prominent citizens from the wealthiest families, this council made decisions on civic affairs, finances, and religious matters. An inscription discovered in the Zeus Olympios sanctuary dated to 9/10 AD references “a decree antecedent of the council,” demonstrating the boule’s early establishment and decision-making authority.

Evidence from the bouleuterion (council chamber) includes inscribed seats with the names of the city’s tribes, indicating that representation in the council was organized along tribal lines. These inscriptions reveal that Zeus, along with other Olympian gods, served as the tutelary divinity for one of the leading urban tribes, underscoring the integration of religious and political structures.

Civic Magistrates

Below the council, various magistrates managed specific aspects of city administration. These supervisors included::

- Archons: Senior officials who presided over civic affairs

- Strategoi: Officials with responsibilities similar to modern city managers

- Agoranomoi: Market officials who regulated commerce, weights, measures, and possibly public lighting

- Astynomoi: Officials responsible for streets, public order, and urban infrastructure

A fascinating inscription from Gerasa mentions that Antonius Marsus, a man of equestrian rank, served as a supervisor in 231-232 AD, though the inscription doesn’t specify what particular area of administration he supervised. This general supervisory role could encompass various public works responsibilities, including construction and maintenance of civic monuments.

The Ecclesia

While evidence is limited, it’s likely that Gerasa maintained the traditional Greek assembly (ecclesia) where male citizens could gather to hear pronouncements and participate in certain civic decisions, though its real power was probably ceremonial by the Roman period.

-> Explore the physical setting of these institutions in our article “Walking Through Ancient Gerasa: A Monument-by-Monument Guide”

Relationship with Rome: Provincial Administration

While Gerasa enjoyed internal autonomy, it operated within the framework of Roman provincial administration. The city’s elite cultivated relationships with Roman governors and officials, often dedicating monuments to demonstrate their loyalty.

Provincial Leadership

The administrative structure of Gerasa changed significantly in 106 AD. Before this date, Gerasa belonged to the province of Syria, governed by Roman officials based in Antioch (modern Antakya, Turkey). From 27 BC onward, these officials held the title of imperial legates (legatus Augusti pro praetore) under Augustus’s new administrative system, though they continued to function as provincial governors. This administrative change explains how figures like Quirinius (Bible Luke2:2) could serve as “governor of Syria” during the early imperial period.

After 106 AD, when Trajan created the province of Arabia, Gerasa was transferred to this new province with its capital at Bostra. The provincial governor now resided at Bostra and held military command and supreme judicial authority over the region.

Regional Administration and Distance Challenges

The considerable distance between provincial capitals and Decapolis cities—approximately 400-500 kilometers from Antioch to Gerasa—presented significant administrative challenges. Rome solved this through intermediate administrative structures.

Archaeological evidence suggests that during the 1st century AD, when Gerasa belonged to Syria, a special administrator was appointed specifically for the Decapolis region. An inscription found in Thrace mentions an anonymous equestrian officer who served as “prefect or procurator of the Decapolis” around 90 AD, indicating there was a dedicated administrative position for governing this region.

An intriguing feature of Gerasa’s administration was the presence of procurators—Roman financial officials—within the city itself, rather than in the provincial capital. Multiple inscriptions discovered in Gerasa mention procurators, both equestrian officials and imperial freedmen, along with subordinates like record-keepers and other staff.

This arrangement suggests that Gerasa served as the administrative center for the Decapolis region, allowing Roman officials to respond quickly to local issues without requiring communication with distant Antioch. Even after the provincial reorganization under Trajan in 106 AD, Gerasa appears to have maintained this administrative importance.

Military Presence

The archaeological record reveals a clear military presence in Gerasa. Auxiliary units were stationed in the city, including the Ala Augusta Thracum (Thracian cavalry wing), as evidenced by several bilingual inscriptions mentioning cavalrymen of this unit. These forces maintained order and likely provided security for the regional Decapolis administration.

Inscriptions from Gerasa mention centurions and other military personnel who integrated into local society. Military service provided a pathway to civic leadership, with some prominent families tracing their rise to centurion ancestors who settled in the city after completing their service.

Division of Authority: Local vs. Roman Control

The presence of Roman procurators in Gerasa created a complex administrative dynamic similar to the situation in Judaea under governors like Pontius Pilate. The practical division of authority appears to have functioned as follows:

Local Boule Retained Control Over:

- Daily municipal affairs: market regulation, local public works, religious festivals

- Local civil disputes between citizens of the same legal status

- Municipal finances: collecting and spending local revenues (though major expenditures might require approval)

- Appointment of local magistrates: agoranomoi, astynomoi, and other civic officials

Roman Procurator/Prefect Controlled:

- Imperial taxation: collection of tribute and provincial taxes

- Major criminal cases: especially those involving Roman citizens or capital crimes

- Military matters: security, rebellion, and major public order issues

- Inter-city disputes: conflicts between different Decapolis cities

- Major infrastructure projects that affected imperial interests

This system worked more smoothly than in Judaea because Gerasa’s Hellenized elite were culturally aligned with Roman values, and the city lacked the intense religious-political conflicts that made other regions volatile. Both sides had incentives to cooperate: local elites maintained their status and handled profitable local affairs, while Roman officials achieved reliable tax collection without excessive administrative burden.

Citizenship and Social Mobility

Roman citizenship was extremely rare among Gerasa’s population during the early imperial period before the First Jewish War (66-73 AD). In this early period, the vast majority of Gerasa’s inhabitants were peregrini (free non-citizens) who retained their local civic status within the Greek polis system.

The few individuals who did hold Roman citizenship during this early period likely acquired it through military service in auxiliary units or through special grants from governors or emperors. These early Roman citizens would have stood out significantly in the community, both for their legal privileges and their distinctive three-part Roman naming conventions.

Archaeological evidence suggests that military service was already emerging as a pathway to citizenship, as Roman auxiliary units were stationed in the region to support the administration of the Decapolis. Veterans who completed their service and received citizenship grants sometimes settled in cities like Gerasa, bringing Roman legal status into local society.

The relative rarity of Roman citizenship in this early period meant that local governance remained firmly in the hands of the traditional Greek civic elite, who operated the polis institutions without needing Roman legal status to maintain their authority and influence within the community.

Civic Euergetism and Public Works

A hallmark of Gerasa’s governance was the system of euergetism—civic benefactions by wealthy citizens who funded public buildings and services in exchange for honor and prestige. This mechanism bridged political administration and urban development.

Numerous inscriptions commemorate these acts of generosity. In the Sanctuary of Zeus, a limestone plaque records the donation of 5,000 drachmas each by Titus Pomponius (of the tribe Scaptia) and his wife Manneia Tertulla. Another inscription from the early 1st century AD honors Démétrios, described as a “founder of the portico,” with a crown for his generous contribution to the sanctuary.

Such benefactions were often connected to religious and civic offices. Démétrios, identified in one inscription as a former priest of Augustus, exemplifies how religious service, political position, and civic benefaction were intertwined in Gerasa’s elite culture.

-> Discover more about city beautification projects in our article “Architectural Features and Building Styles”

Tribal and Familial Affiliations

Gerasa’s social organization included tribal divisions that influenced political representation. Inscriptions from the bouleuterion (council chamber) reveal seat allocations for different tribes, each associated with particular deities.

Elite families dominated civic offices across generations. Epigraphic evidence shows recurring names like Démétrios and Antonius among the city’s leading citizens and religious officials. The presence of three-part names (including grandfather’s name) in many inscriptions demonstrates the importance of lineage in establishing social and political legitimacy.

Public Financing and Economic Administration

The city’s administration managed various revenues to fund public services and infrastructure:

- Market taxes and duties regulated by market officials (agoranomoi)

- Rents from city-owned properties and lands

- Fees from markets and commercial activities

- Benefactions from wealthy citizens

- Imperial grants for specific projects

Financial matters were handled by dedicated officials and carefully recorded. The presence of Roman procurators and their staff in the city points to the importance of financial administration in Gerasa’s governance system.

Religious Administration

Religion and politics were inseparable in Gerasa. The city maintained priesthoods for various deities, with the cult of Zeus Olympios being particularly prominent. Epigraphic evidence also shows the establishment of the imperial cult in Gerasa from the Augustan period onward.

Inscriptions mention priests of Augustus, Nero, and Trajan, indicating that imperial cult priesthoods were prestigious positions held by members of leading families. These religious roles reinforced the connection between the local elite and Roman authority.

Gerasa’s administrative system exemplifies how a provincial city could maintain local autonomy while integrating into the broader Roman imperial framework. The city’s governance combined Greek political traditions, Roman administrative structures, and local religious and tribal affiliations, creating a distinctive civic identity that supported its remarkable urban development during the first two centuries AD.

As visitors walked through the colonnaded streets of Gerasa, they would have encountered not just impressive architectural achievements but the visible manifestations of this sophisticated administrative system—from inscriptions honoring benefactors to the bouleuterion where the council met, from temples serving as centers of civic identity to the buildings housing Roman officials who linked the city to the wider imperial network.

Sources: “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik “Dédicaces de statues ‘portes-flambeaux’ (Δαιδουχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne “Jerash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker “Onomastique et presence Romaine a Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier “The Chora of Gerasa/Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas, Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja “New Perspectives on the City on the Gold River” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa / Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja