Note: This article merges archaeological and historical evidence from approximately 1-200 AD to provide a comprehensive overview of Gerasa’s urban development during the early Roman period.

The Birth of a Roman City

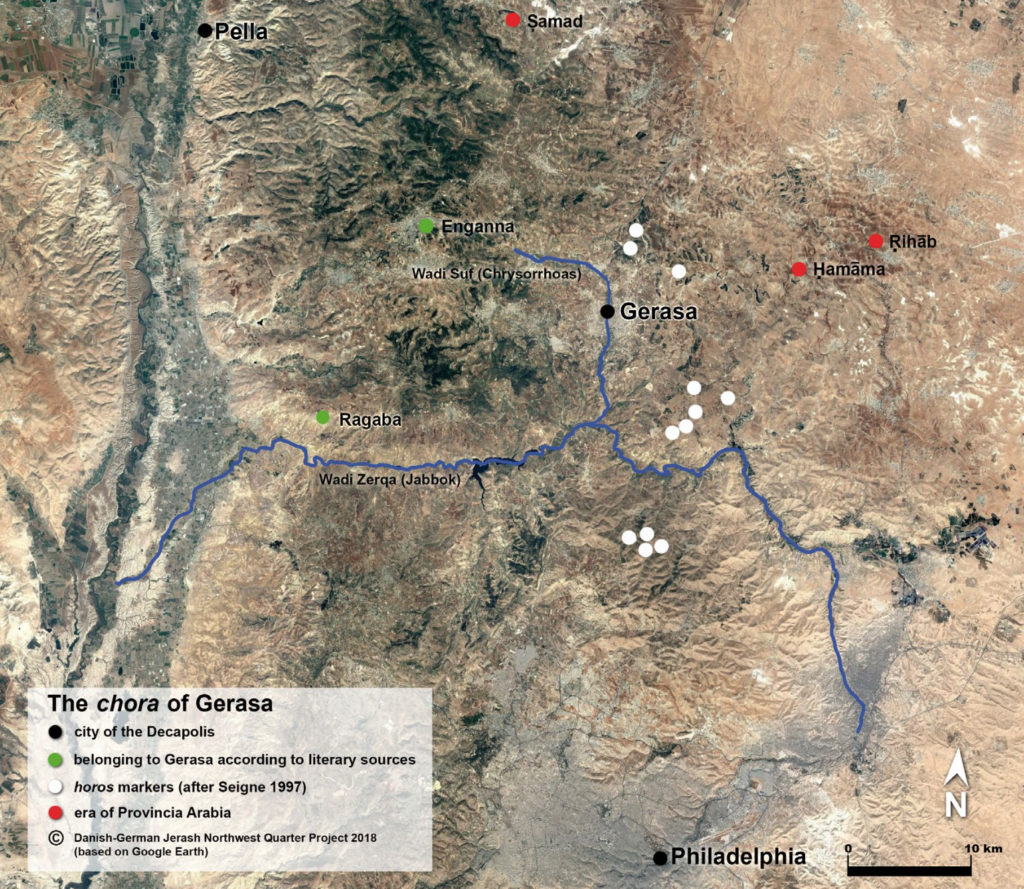

By the dawn of the first century AD, Gerasa—also known by its Seleucid designation “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas”—was entering a transformative period. Though the site had been inhabited since prehistoric times, with evidence of Neolithic settlements nearby, it was during the first two centuries AD that Gerasa truly blossomed into the magnificent city whose ruins still impress visitors today.

The city underwent extensive development following Pompey’s conquest in 63 BC, when it was incorporated into the newly created Roman province of Syria. This political transition marked the beginning of unprecedented urban prosperity and expansion, particularly from the late 1st century BC through the 2nd century AD. Archaeological evidence reveals that this period witnessed a tremendous surge in monumental building activity that would define the city’s character for centuries to come.

The Urban Armature: Streets and Quarters

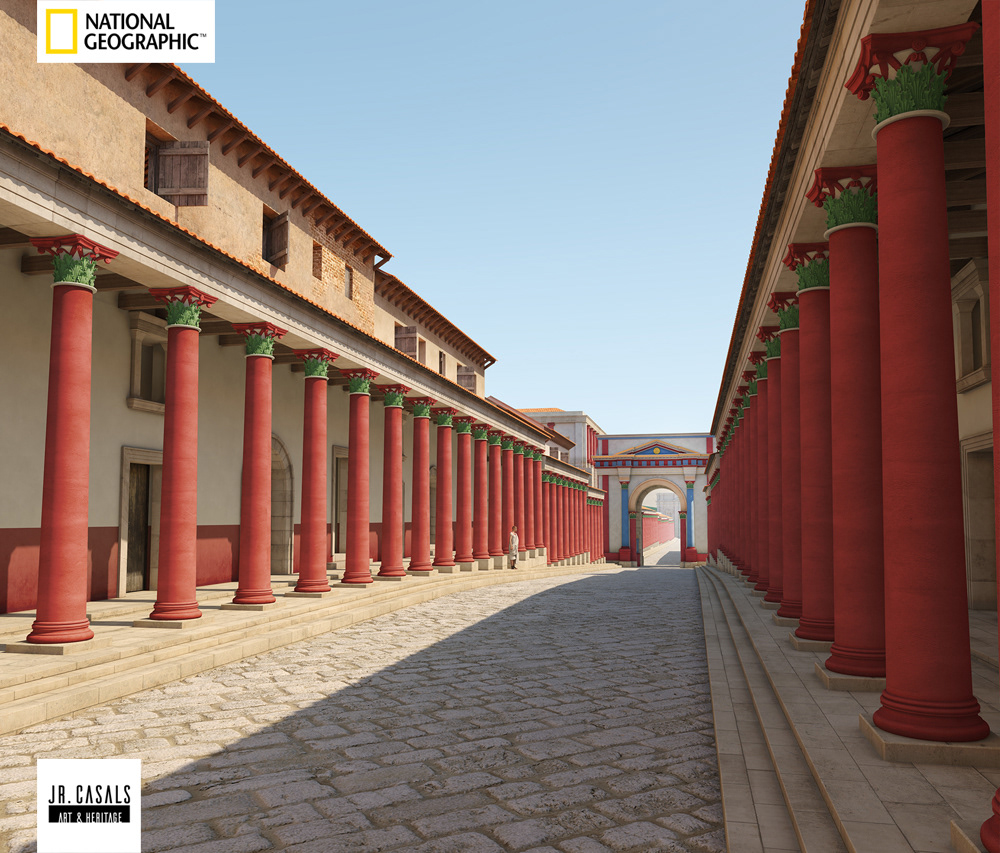

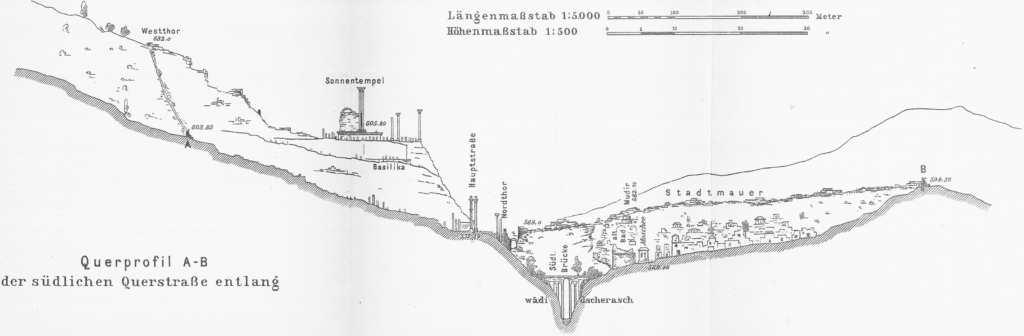

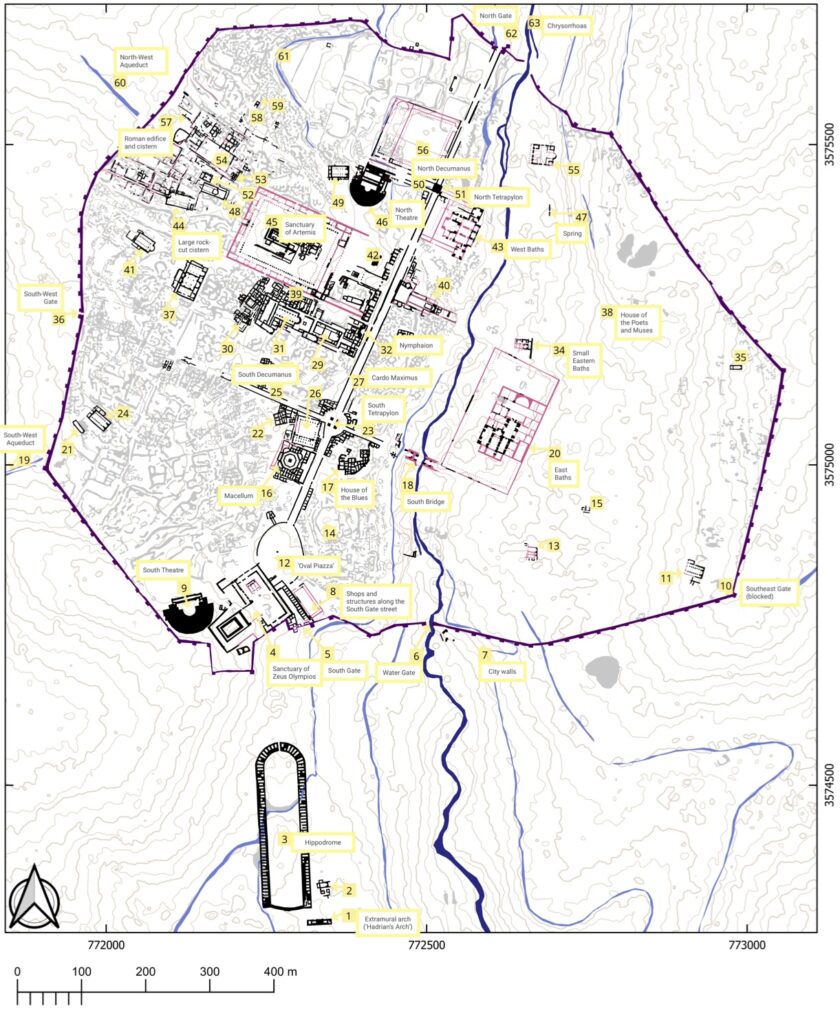

The heart of Roman Gerasa was structured around a monumental colonnaded street running north-south for approximately 1.2 kilometers. This main thoroughfare, known today as the Cardo Maximus, was developed in the 1st century AD and served as the organizing spine of the entire city. Paved with limestone slabs worn smooth by generations of sandals and cart wheels, the Cardo was flanked by impressive Corinthian columns supporting covered porticoes that sheltered pedestrians and shopkeepers from the Mediterranean sun.

From this central artery, two major east-west streets (decumani) branched off perpendicularly, dividing the city into distinctive quarters. The North Decumanus was a particularly significant thoroughfare, though archaeological research has revealed that it did not extend all the way to the western city wall as was once believed. Recent excavations in the Northwest Quarter by the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project have shed new light on this area, which sits at the highest point within the walled city.

The city’s urban grid, while adhering to classical Roman urban planning principles of orthogonal streets, was necessarily adapted to the natural topography of the site. The eastern half of the city occupied gently sloping terrain down to the Chrysorrhoas River, while the western half, including the Northwest Quarter, rose more steeply toward the surrounding hills. This topographical variation required innovative solutions for street layout, water management, and monumental architecture.

Defensive Works: Walls, Gates, and Security

Encircling the urban core, Gerasa’s impressive city walls stretched approximately 3.4 kilometers, enclosing an area of about 90 hectares at the height of the city’s development. The walls were punctuated by several monumental gates that controlled access to the city while also serving as impressive architectural statements of civic pride and imperial power.

The most dramatic of these entrances was the South Gate, which welcomed travelers arriving from Philadelphia (modern Amman). Just beyond this gate stood the massive Hadrianic Arch, constructed to commemorate Emperor Hadrian’s visit to the city in 129/130 AD—a testament to Gerasa’s importance within the provincial framework of Roman Syria, and later (after 106 AD) the province of Arabia.

Other significant access points included the North Gate, leading toward Pella, and gates to the east and west. Each served not only defensive purposes but also as monumental transitions between the urban core and its periphery, where cemeteries, quarries, and agricultural lands lay.

Civic and Religious Centers

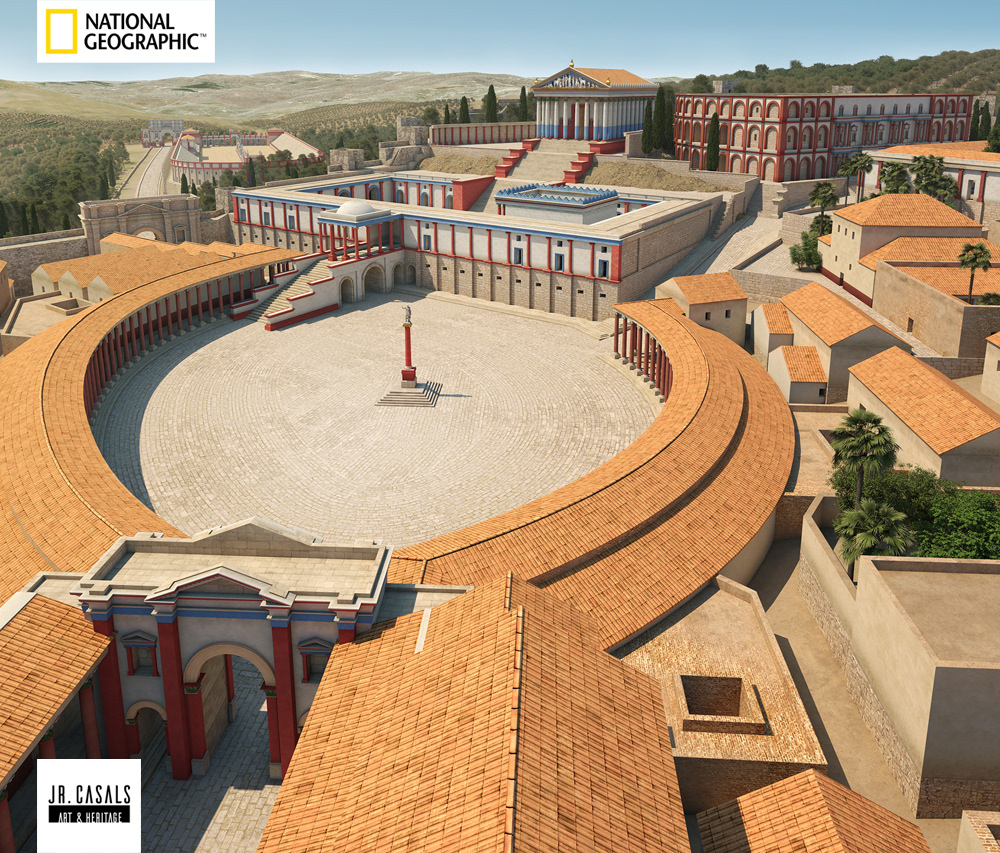

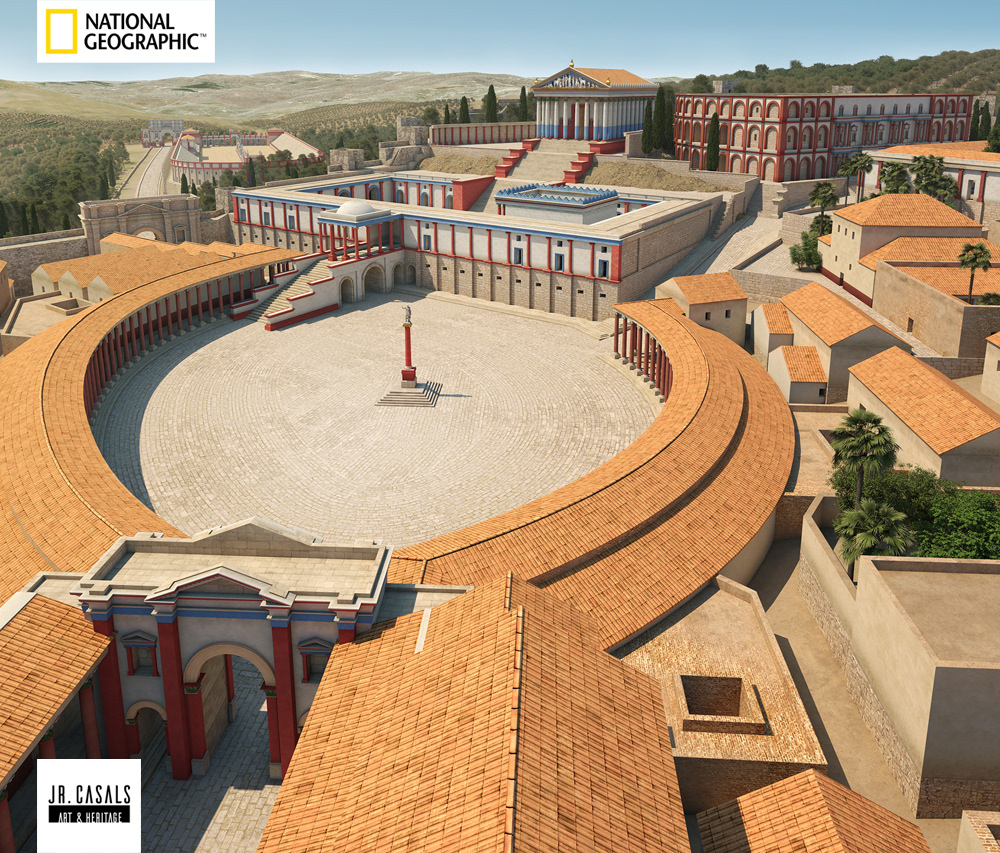

The heart of public life in Gerasa centered around several monumental spaces strategically placed along the Cardo. Near the southern end of the main street lay the remarkable Oval Plaza (Forum), a unique architectural feature among cities of the Eastern provinces. This elliptical space, paved with limestone and surrounded by a colonnade, served as a transitional element between the main street and the Sanctuary of Zeus.

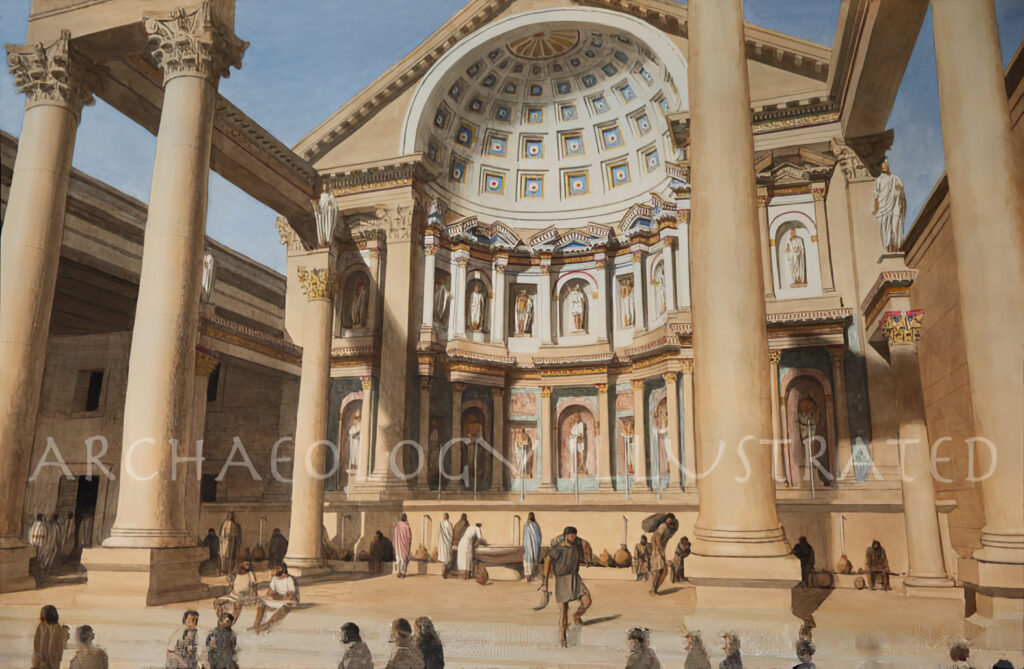

The Sanctuary of Zeus occupied a prominent position on a hill overlooking the Oval Plaza, with construction phases dating back to the late Hellenistic period. This complex expanded significantly during the 1st-2nd centuries AD, reflecting both religious devotion and civic pride. The sanctuary consisted of a lower terrace with a monumental gateway and an upper terrace dominated by the temple itself. French archaeological teams have worked extensively at this site, uncovering evidence of sophisticated architectural and engineering solutions that enabled the sanctuary’s expansion on challenging terrain.

On the opposite side of the city, the massive Sanctuary of Artemis dominated the western skyline. Built in the 2nd century AD, this complex featured a monumental entrance from the Cardo, leading to a colonnaded courtyard and ultimately to the temple itself, which stood atop a high podium. As the patron goddess of Gerasa, Artemis received particular veneration, reflected in the scale and splendor of her sanctuary.

Between these primary religious complexes lay the city’s civic infrastructure: a macellum (market), multiple bath complexes including the impressive Great Eastern Baths, and a pair of theaters. The southern theater, with a capacity of approximately 3,000 spectators, was constructed in the late 1st century AD and hosted theatrical performances, musical competitions, and civic gatherings. The northern theater, slightly smaller, likely served as a bouleuterion or odeon—a council chamber and performance space where the city’s elite conducted business and enjoyed cultural events.

Residential Districts and Neighborhoods

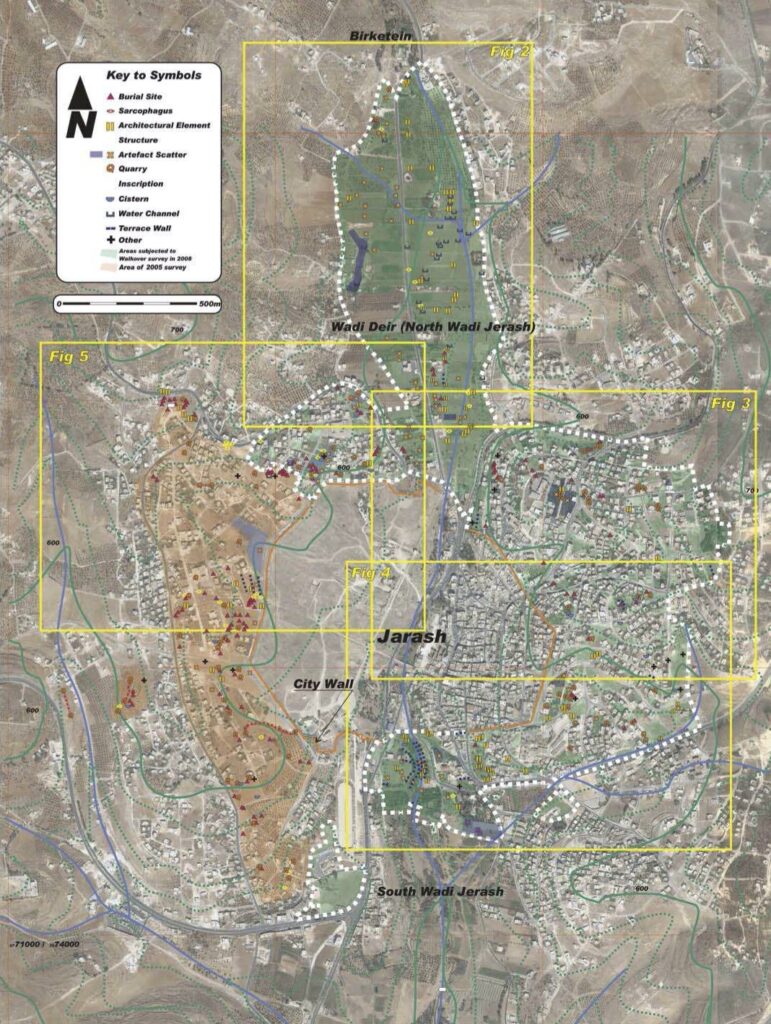

While the monumental structures along the Cardo have received the most archaeological attention, the residential areas of Gerasa occupied the majority of the walled urban space. These neighborhoods showed considerable variation in layout, density, and quality depending on their location within the city.

Elite residences tended to occupy prime locations on elevated terrain with views, particularly in the western sectors of the city. Archaeological evidence suggests these homes featured peristyle courtyards, private water systems, and decorative elements like mosaics and wall paintings. Middle and lower-class housing was likely concentrated in more densely packed neighborhoods with narrower streets and simpler construction techniques.

The Northwest Quarter, situated at the highest point within the city walls, has revealed evidence of both monumental architecture and residential occupation during the Roman period, though the area lacks extensive evidence of Hellenistic and early Roman monumental public architecture. Excavations here have uncovered a cycle of construction, destruction, demolition, and reuse spanning many centuries, indicating the dynamic nature of urban development even in the city’s periphery.

Urban Infrastructure and Services

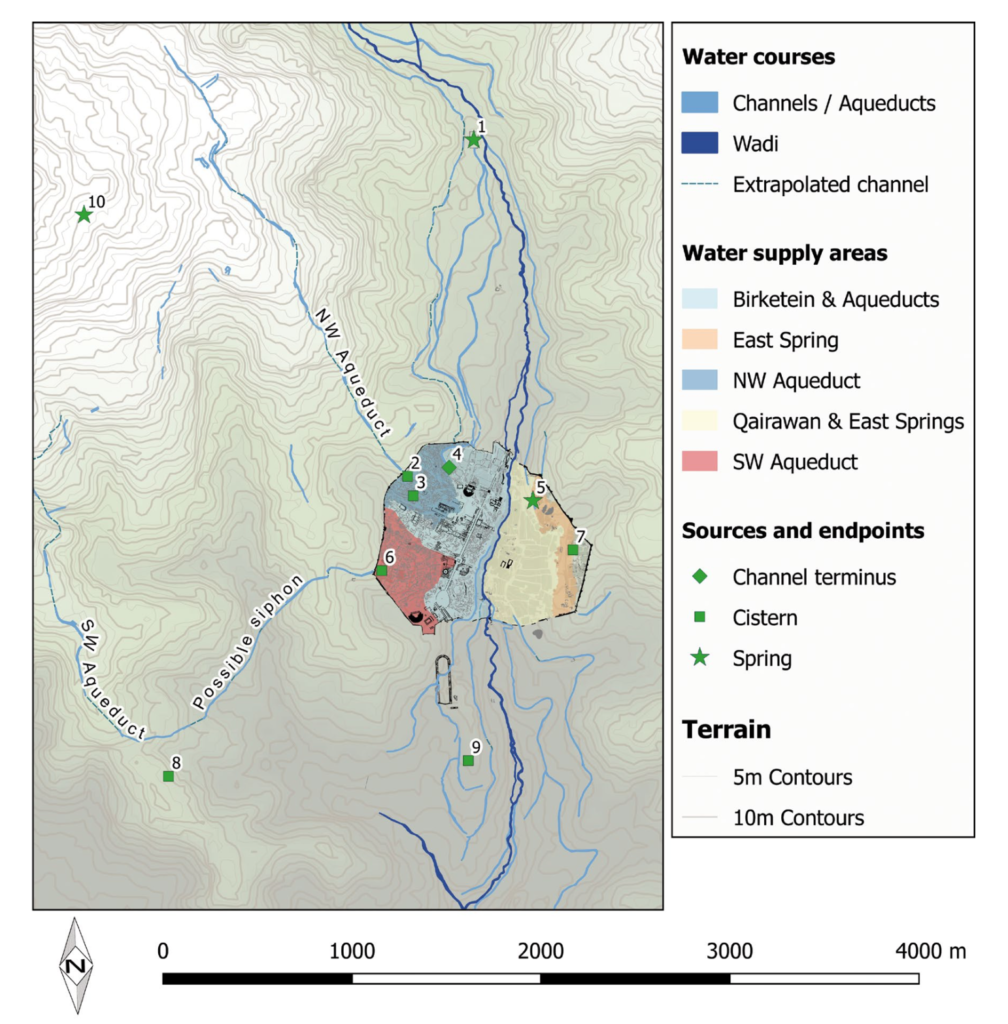

Roman Gerasa boasted sophisticated infrastructure systems that supported its dense urban population. Water management was particularly critical, given the Mediterranean climate with its seasonal rainfall patterns. The city’s engineers built elaborate systems to collect, store, and distribute water throughout the urban environment.

Water was supplied to Gerasa primarily from springs, particularly those at Suf approximately 7km northwest of the city. Archaeological surveys have identified Roman aqueducts that channeled this water to the city, where it was then distributed through a network of pipes and channels. Small rock-cut canals managed runoff and directed water to cisterns for storage during dry periods.

The city’s commitment to public services extended to sanitation and bathing facilities. The Great Eastern Baths, representing one of the largest such complexes in the region, featured a sequence of rooms with different water temperatures, allowing citizens to progress through the traditional Roman bathing ritual. These facilities served not only hygienic purposes but also important social functions as gathering places for citizens of all classes.

Development Through Time

The urban fabric of Gerasa was not static but evolved considerably throughout the first two centuries AD. Archaeological evidence indicates three major phases of development during this period:

- Early 1st century AD: Initial development of the basic urban framework, including the main colonnaded street and essential public buildings.

- Late 1st to early 2nd century AD: Expansion and embellishment during the reigns of the Flavian emperors through Trajan, including the construction of the South Theater and the initial phases of both major sanctuaries.

- Hadrianic through Antonine periods (117-192 AD): The apex of Gerasa’s monumental development, featuring the construction of the Artemis complex, the expansion of the Zeus sanctuary, and the addition of numerous civic buildings.

This progressive development reflected the city’s growing prosperity and deepening integration into the provincial and imperial systems of the Roman East. The transition from the province of Syria to the newly created province of Arabia in 106 AD appears to have further accelerated Gerasa’s urban development, possibly due to its strategic position within the new provincial framework.

Beyond the Walls: Suburbs and Peripheral Areas

Gerasa’s urban influence extended well beyond its impressive walls. The immediate periphery contained critical elements of the city’s infrastructure and economy: cemeteries lined the roads approaching the gates, following Roman custom of extraurban burial; quarries that supplied the city’s seemingly insatiable demand for limestone dotted the surrounding hillsides; and agricultural installations such as olive presses and mills occupied the fertile areas adjacent to the Chrysorrhoas River.

Of particular note was the area of Birketein, located approximately 2km north of the city. This site featured a reservoir and sanctuary, likely connected to water-related religious festivals. The presence of a small theater here suggests its use for seasonal ceremonies and celebrations that complemented the religious calendar of the main urban sanctuaries.

Conclusion

The urban layout of Gerasa during the first two centuries AD reflects a remarkable synthesis of Roman planning principles with local topographical and cultural realities. From its monumental colonnaded street to its impressive sanctuaries and sophisticated infrastructure systems, the city embodied the ambitions of a prosperous provincial center eager to display its participation in the broader cultural and political frameworks of the Roman Empire.

As you walk through the archaeological site today, the underlying logic of the ancient city remains visible in the alignment of columns, the positioning of monuments, and the flow of streets. These physical remnants speak to a vibrant urban community that, for over two centuries, built, maintained, and expanded one of the most impressive cities of the Roman East—a legacy of stone that continues to inspire wonder two millennia later.

Disclaimer:

All images used in this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja