Note: This article combines archaeological and historical evidence spanning from Gerasa’s early development through the 2nd century AD to present a comprehensive picture of the city’s geographical setting.

The ancient city of Gerasa, modern-day Jerash in Jordan, flourished as one of the most prestigious Decapolis cities during the Roman period. The city’s remarkable state of preservation offers us a window into the past, but to truly understand Gerasa, we must first understand the land that shaped it. The physical setting of Gerasa didn’t just influence where the city was built—it fundamentally determined how it developed, how its inhabitants lived, and why it prospered as a regional center.

A Landscape Shaped by Water

The single most important geographical feature of Gerasa was undoubtedly its relationship with water. The city was built on both banks of a river known in antiquity as the Chrysorrhoas, or “Gold River.” This name likely referred either to the rich agricultural bounty it helped produce or perhaps to its appearance when carrying abundant harvests downstream. Today this waterway is called Wadi Jerash.

The Chrysorrhoas had its origins in springs located approximately 7 kilometers northwest of the ancient city at a place called Suf. From there, it flowed toward Gerasa and continued southward for another 6 kilometers before joining the Wadi Zarqa (known in biblical times as the River Jabbok). The valley of the Chrysorrhoas was exceptionally fertile, particularly its upper portion between Gerasa and the springs.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest settlement at Gerasa was established near a perennial spring, taking advantage of this reliable water source. The city’s founders surely understood that consistent access to fresh water was essential not only for drinking but also for agriculture, industry, and sanitation.

Topography and Defensive Position

Gerasa was situated in the fertile hill country of northwestern Jordan, in terrain characterized by a calcretized conglomerate formation. This landscape featured:

- A series of rolling hills with one particular prominence that would later host the Temple of Zeus

- The Northwest Quarter, which represented the highest point within the walled city

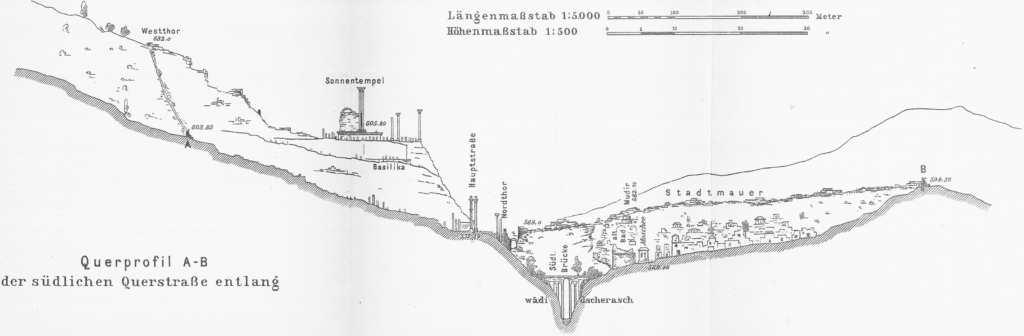

- A significant drop in elevation from west to east, with the Chrysorrhoas running through the middle

- Naturally defensible positions that could be further enhanced with walls

The topographical layout of Gerasa presents a classic example of site selection in the ancient world—a balance between access to resources and defensibility. The city was built across several hills and valleys, with the valley of the Chrysorrhoas providing a natural division between the eastern and western parts of the urban area.

This hilly terrain created both challenges and opportunities for urban development. While it complicated city planning and construction, requiring terracing and innovative architectural solutions, it also provided natural drainage for waste and stormwater, improving overall sanitation conditions compared to cities on flat terrain.

Climate and Seasonal Patterns

The climate of Gerasa during the Roman period was similar to what the region experiences today—a Mediterranean climate characterized by:

- Hot, dry summers

- Mild, wet winters

- Approximately 400mm of annual rainfall, primarily occurring between November and April

- Occasional heavy downpours that could cause flash flooding in the wadi

This climate pattern significantly influenced the daily rhythms of life in Gerasa, as well as its agriculture and water management practices. The seasonal nature of rainfall necessitated careful water storage and distribution systems throughout the city.

Surrounding Environment and Resources

Beyond the immediate vicinity of the city, the landscape provided a range of resources vital to Gerasa’s development and prosperity:

Vegetation

The surrounding region supported a Mediterranean vegetation pattern that included:

- Native forest areas with pine and terebinth trees

- Non-forest Mediterranean vegetation in areas subject to human activity

- Agricultural areas where the natural vegetation had been cleared

Archaeological and palynological evidence suggests that deforestation was already occurring during this period, likely to clear land for agriculture and to provide timber for construction and fuel.

Geology and Building Materials

Gerasa’s built environment was heavily dependent on local geological resources:

- Local limestone served as the primary building material for most structures

- Hard white or pink limestone was used for prestigious public buildings

- Softer whitish limestone was employed for more mundane construction

- Clay deposits in the region supported local pottery production

- Sand and other materials necessary for mortar and concrete were readily available

Quarrying activity is evidenced throughout the area surrounding Gerasa, with ancient quarry sites still visible in the landscape today. The sophisticated stone-working techniques employed by Gerasene builders demonstrate their mastery in adapting local materials to ambitious architectural projects.

Strategic Position Within Regional Networks

Gerasa’s location granted it strategic importance within the broader regional context:

- Positioned on trade routes connecting the Mediterranean coast to Arabia and Mesopotamia

- Near enough to the Via Nova Traiana (built in 111-114 AD) to benefit from this major north-south highway

- Situated within a network of roads connecting to other Decapolis cities

- Located at a comfortable day’s journey from neighboring urban centers

This advantageous positioning contributed significantly to Gerasa’s economic development, allowing it to serve as a commercial hub where goods from different regions could be exchanged.

Agricultural Hinterland

The territory controlled by Gerasa—its chora—extended beyond the urban center to encompass a productive agricultural hinterland. This area included:

- Terraced slopes for olive cultivation

- Valley floors suitable for grain production

- Grazing lands for livestock

- Numerous rural settlements and farming estates

Archaeological surveys have identified scattered sites throughout the surrounding territory, including farmsteads, villas, watchtowers, and small villages that were economically and administratively tied to the city.

The fertility of this hinterland was crucial to Gerasa’s prosperity. An inscription discovered in the Northern Theater mentions “gardeners of the upper valley,” suggesting that the fertile lands along the Chrysorrhoas were intensively cultivated, likely producing fruits and vegetables for the urban market.

Conclusion

The physical geography of Gerasa—its water resources, topography, climate, and strategic position—created the foundation upon which a thriving urban center could develop. When Roman influence arrived in the region, these geographical advantages were further enhanced through sophisticated engineering and urban planning.

Understanding the geographical context of Gerasa helps us appreciate how deeply the city’s development was rooted in its natural setting. As we explore other aspects of life in this remarkable ancient city, we’ll continue to see how its geography shaped everything from its economic activities to its religious practices, from its architecture to the daily lives of its inhabitants.

Disclaimer:

All images used on this article are the property of their respective owners. I do not claim ownership of any images and provide proper attribution and links to the original sources when applicable. If you are the owner of an image, please contact us so I can add your information or remove it if you wish.

Sources:

- “Official Guide to Jerash” with plan by Gerald Lankester

- “The Chora of Gerasa Jerash” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas Formerly Called Gerasa” by Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Jarash Hinterland Survey — 2005 and 2008” by David Kennedy and Fiona Baker

- “A new inscribed amulet from Gerasa (Jerash)” by Richard L. Gordon, Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja

- “Apollo and Artemis in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “Onomastique et présence Romaine à Gerasa” by Pierre-Louis Gatier

- “Dédicaces de statues “porte-flambeaux” (δαιδοῦχοι) à Gerasa (Jerash, Jordanie)” by Sandrine Agusta-Boularot and Jacques Seigne

- “Un exceptionnel document d’architecture à Gérasa (Jérash, Jordanie)” by Pierre-Louis Gatier and Jacques Seigne

- “Zeus in the Decapolis” by Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik

- “The Great Eastern Baths at Gerasa Jarash” by Thomas Lepaon and Thomas Maria Weber-Karyotakis

- “Architectural Elements Wall Paintings and Mosaics” by Achim Lichtenberger

- “Glass Lamps and Jerash Bowls” by Rubina Raja

- “Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland” by David D. Boyer

- “Hellenistic and Roman Gerasa” by Rubina Raja